This is a love story. This is the story of how I fell in love with poetry and what it can do to me. Is it going to be corny? Oh hell yes.

So let’s get in this TARDIS over here, the dingy one that doesn’t change much from season that’s piloted by the Doctor with the toothy grin and the extremely long scarf and let’s go back to 1986 or so, where I am in Ms. Nancy McKee’s 11th grade American Literature class.

It’s hot, but that doesn’t say much about the time of year because it’s always hot in Slidell except for maybe 3 weeks out of the year and it’s not then. But I can tell you that it’s early spring on the calendar because we’re reading things that were written in the 20th century: Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Sherwood Anderson maybe? It’s been a while. Most of us don’t care, even the literarily-minded among us.

My experience of poetry up to this point had either been religious, as in the Psalms which didn’t really read like poetry to me, or very formal. In 10th grade our poetry section was all about scansion and forms and it felt like a game, a game I was pretty good at, but still a game. Could I make combinations of words where the accents hit in the correct places and the lines break where they’re supposed to? Absolutely. It was a puzzle and I can solve puzzles. But I wasn’t writing poems. I was making words fit together in reasonably pleasing ways.

That day in Ms. McKee’s class, I don’t know if she had always planned to do this or if she just called an audible because she was tired of us being visibly bored and edgy, and I don’t even remember how she got into this place because I was not paying attention. I was probably reading a Heinlein novel? I did a lot of that in class. But I look up and she’s writing, from memory, the opening lines of “in Just-” by E. E. Cummings.

This is what makes me believe she was just throwing something at the wall to try to get our attention. She was writing it on the board from memory and she was forgetting pieces of it and telling us that in the moment. It was not a poem in our textbook. Of course it wasn’t.

I woke up to what was going on around the time she wrote “mud-luscious” on the board and by the time she got to the way the balloonman moves from lame to queer to goat-footed I was sold. I was like “you can DO that in a poem?”

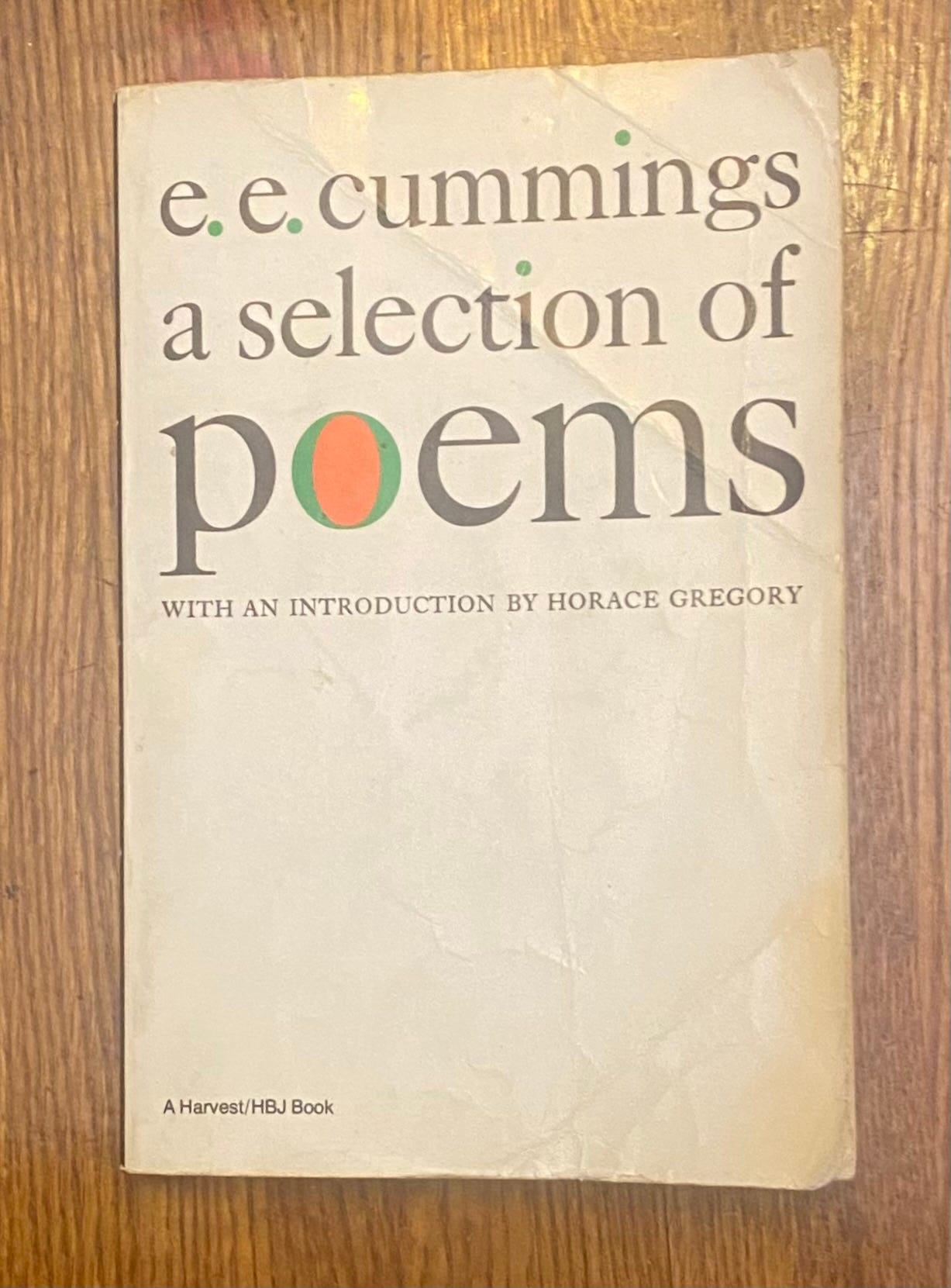

I hit the school library but there’s no Cummings. Same for the public library branch near our trailer. So I ride my bike to the one bookstore we had in Slidell, Louisiana at the time and find their poetry section and there’s no Cummings so I go to the counter and a guy pulls out a catalog with a bunch of titles looking like entries in the White Pages (ask your parents? grandparents?) and runs his finger down the page and says “oh, we can get you this one. It’ll take a couple of weeks and you have to pay up front.”

So I dig the dollars I made slinging fried chicken 25 hours a week out of my pocket and give it to him along with my phone number and then spend the next two weeks waiting and wondering if I’m going to be home when the phone rings because we don’t have an answering machine and what if my mom or dad answers the phone and then I have to tell them I ordered a book of poems and they then might insist on reading it first to make sure it’s appropriate and not too worldly and all I know of this book is part of one poem and who knows if maybe there are swear words in other poems I don’t know and besides all that this is mine.

This is mine. I don’t want anyone else in this house to read this before I do. I don’t want them to even know about it. I am not exaggerating when I say I would rather my parents find the shoplifted copies of Penthouse Letters stuffed between my mattress and box springs than discover I have ordered this book of poems.

The poetry gods pity me and the bookstore calls after I’ve gotten home from school but before my dad has gotten home from his door-to-door preaching and my mom has gotten home from work and I jump on my bike and pick up my contraband and I don’t even wait until I get home to start. In the next parking lot over there was a little gathering of stores and a bench under some shade and I stopped there to read this book.

That’s the literal book, still with me after 37 years and countless moves. $4.95 plus tax. I flip through it looking for the poem and there it was on page 25 and I stared at it amazed that my 11th grade English teacher Ms. Nancy McKee had indeed not been making shit up about what poems could look like.

The funny thing is that “in-Just” is fairly tame in terms of playing with space on the page and jamming words together, but to me whose experience of poetry in classes had been heaping helpings of Edgar Allan Poe and Shakespeare and William Cullen Bryant’s “Thanatopsis” (no idea why that poem stuck—no wait, I do. When we were reading it aloud in class, I accidentally switched out the word “penis” for “pensive.” I believe to this day that my best friend Geoff shot that word telepathically into my brain at that moment to embarrass me.) it was life-changing.

For weeks afterward I devoured the 188 pages of that book. I leaned heavily at first toward the ones that looked stranger on the page because that’s neat, that’s cool, that’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen before. I want to do that, I thought. I sat at my mom’s word processor and mashed words together and wrapped short lines in parentheses to create double readings and shot individual words out to the right margin for no other reason other than I liked how it looked.

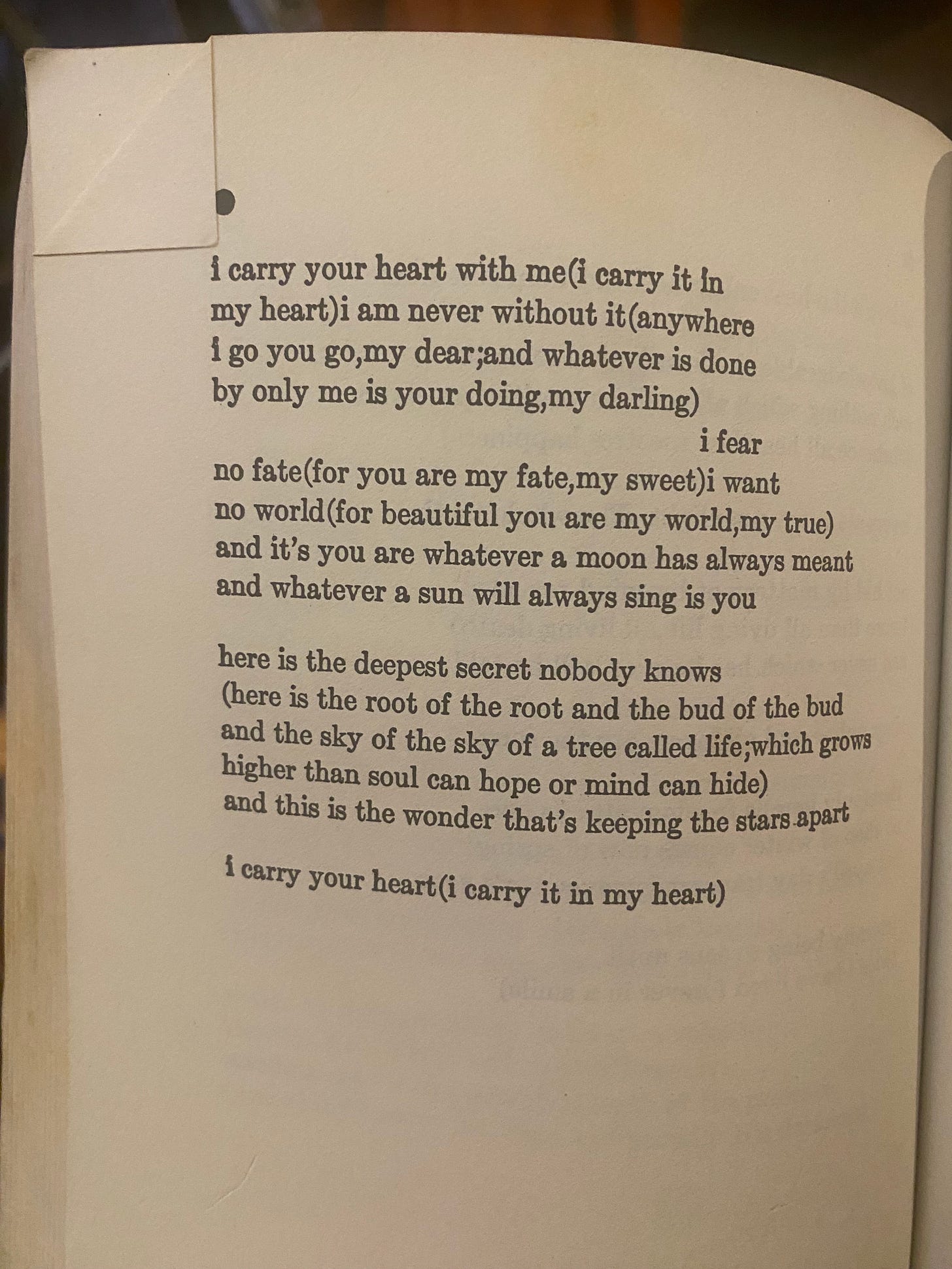

But I also read the poems that looked like poems, especially the shorter ones, the ones I wouldn’t realize until years later, maybe over a decade when I was finally in graduate school were all fourteen lines long and rhymed in sometimes regular sometimes irregular ways and eventually I started dog-earing those pages too and coming back to them.

(Proof of the poet’s terrible book-handling habits)

And so on. That’s maybe his most famous sonnet. It’s been recited in multiple movies which is more than most poems can ever aspire to. But there’s also the heartbreaking one which starts “it may not always be so” and the very horny “my girl’s tall with hard long eyes” and “i like my body when it is with your body” and the one that ends “—but never fear(my own,my beautiful / my blossoming)for also then’s until.” Eventually those were the ones I read over and over, the love sonnets, the so sentimental that if you try quoting them at someone you want to get with you seriously risk getting laughed at but oh if it works? I wanted to write those poems.

And I did. I have. I do. Never on that level but that’s not the point. I am here proclaiming that those poems are great and that everyone who hangs onto the idea that poems have to be at least partially dipped in irony needs to just revel in corny-ass love once in a while.

I don’t read enough recently-published individual poems (as compared to collections) to know this for certain, but it feels to me like the unabashed love poem is in resurgence, if it ever even went away. Or maybe that’s just the books I’m reading. But oh do I love it.

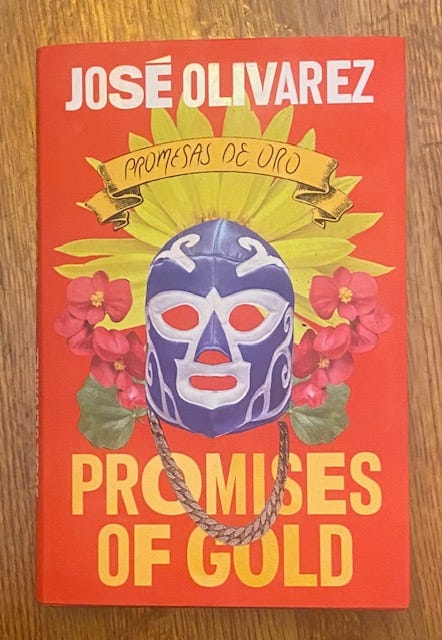

“Love Poem Beginning with a Yellow Cab” by José Olivarez is one of these poems. I read it when I was reading his new book Promises of Gold / Promesas de Oro with the Rumpus Poetry Book Club recently, but the link above takes you to Lithub where it was recently published along with audio of José reading it in English.

I specify that because Promises of Gold is a bilingual book with Spanish translations by David Ruano González, and look, my Spanish is only Duolingo-okay, but the ones I read aloud to myself in my tragic accent were gorgeous. It’s a great book all the way through. Go get a copy.

.

“Love Poem Beginning with a Yellow Cab” is dedicated to José’s wife Erika and the poem begins with him recounting a conversation. “i ask you what’s the first thing you think about / when you see the color yellow & like a real / new yorker, you say yellow cabs.” Now you might look at that capitalization and think “oh, that’s why Brian chose this poem” but I swear by all flowers I didn’t even realize that when I chose this poem and then decided to pair it with my origin story.

I chose it in large part because this poem does something that most Cummings’ love poems don’t. It centers the beloved but doesn’t put her on a pedestal for worship the way so many love poems do. Erika is a whole person here, with observations about her world that spark in the speaker.

Jose continues “not sunlight / or a yellow ribbon tied around a vase of fresh begonias. / yellow cabs honking down Broadway.” His images fall more into the world of traditional love poems: sunlight, flowers, the yellow ribbon for me echoes that Tony Orlando and Dawn song from my childhood which I’m trying to not let get stuck in my head right now and failing where the ribbon stands for a sign that the relationship is still viable. But her image, the yellow cabs in motion, noisy, lively, active, is a striking contrast to the expected.

He describes the first night they shared a cab and then remarks “all that practice & it turns out, i had never ridden / in a cab the right way” and that feels like the pivot to me, the line the rest of the poem rotates around. There’s a sense of respectful awe in that line, the feeling that this is a person who will be a wonder for a long time. The idea that there’s a right way to ride in a cab where you can experience something more than just a ride.

And it’s important that this is a cab, a yellow cab beyond just the color connection. A yellow cab is an icon of New York, of cabs anywhere. It’s not a car service or a private vehicle driven by a gig worker. It’s symbolic of human connection in a way those other conveyances are not, and that’s what this poem is all about in the end.

I’m trying hard to not over-quote this poem to y’all because I want to respect the places that published it, so I’m going to skip the lines about the thighs and hands (though they’re really my favorites in the poem) so I can get you to this ending.

maybe god invented yellow for the cabs,so the first time we touched like thisit could be accented in gold.

This poem begins, as it had to, with two people and ends in we, and I include the cab in the we there because it feels to me like an integral part of the relationship. That’s how they exist forever in this poem, encased in yellow, accented in gold, honking down busy streets energetically, madly in love with each other and the world.

And the we really is important in love poems, because it’s real easy to fall into the trap of making the beloved an object of worship which is both tired and dehumanizing. People don’t go on pedestals. Statues do. Often not even a whole body, just a bust. You don’t love a statue, not even if you’re Pygmalion. The best love poems end in we. They end in this connected space where everyone is alive and real and amazing and flawed and human.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this piece. I’d love to hear about your favorite love poems, the less well-known the better. Give me your deep cuts. Help me find another poem to love.

One of my favorite love poems I can't find online anywhere. It's Marilyn Hacker's Dusk: July. It's sort of long, so I'm not going to type out the whole thing, but here's the last stanza:

I just want to wake up beside my love who

wakes beside me. One of us will die sooner;

one of us is going to outlive the other,

but we're alive now.

Such a beautiful piece, Brian. I love the idea of poems as contraband - the illicit ownership. When I was a kid I borrowed a book of Keats from the library and hid it in my bedroom so no one could see it or see me when I read it, so I think I get a little of what you're saying here and e e cummings is undeniable.

I am now very keen to get my hands on José Olivarez's book; what a beautiful poem. Your analysis (the pivot line, the "we" ending) opened it up for me; thank you!

Charles Simic has been one of my very favourites for years now and I was very sad to hear he passed at the beginning of the year. All of his "back of the envelope" scribbles hold a deep magic. I especially like "Evening Walk".

Happy heart, what heavy steps you take / As you hurry after them in the thickening

shadows.