It’s 2004 and we’re living in San Francisco thanks to the generosity of the Stegner Fellowship and Stanford University but while the stipend is generous this is also San Francisco and even if it’s San Francisco during the brief lull in insane housing prices between the last dot-com bust and the next dotcom boom the stipend alone isn’t enough even for a one-bedroom apartment above a bar on the not-fashionable end of Mission Street so side jobs were required. At first I parked cars for a valet service and to the extent that I can still parallel park, that’s how I learned, in the crucible of having to reverse uphill driving a stick with my knees crammed under my chin because you never NEVER touched the customer’s seat position.

Amy answered a kind of vague Craigslist ad that turned into an interview with a headhunter that turned into an interview with what turned out to be at the time one of the best working-class places in San Francisco, a brewery on Potrero Hill owned by an eccentric heir to an appliance/blue cheese fortune. The owner was Fritz Maytag and the brewery was Anchor Brewing, maker of Anchor Steam beer

.

Anchor Brewing announced a couple of weeks ago that it’s shutting down and going into liquidation. The articles I’ve read about it say that it was the pandemic that finally did it in, since a lot of Anchor’s sales were in restaurants and bars, and that it never really recovered from that loss. There have been some vague gestures to changing drinking habits also having an effect. But most of them basically blame Sapporo for trying to make Anchor into something it wasn’t. There’s currently an attempt by some of the last workers to purchase it from Sapporo and turn it into a worker-owned co-op. This article seems to suggest there’s a chance it could work and I wish them the best.

I also think Anchor was kind of a victim of its own success. When Fritz Maytag bought into Anchor as a Stanford grad student in the late 1960’s, the brewery was trying to sell its equipment in order to make payroll one last time. He first bought in and then bought out the brewery, and while he didn’t know anything about brewing, he focused on making the beer taste the same every time they brewed it. A lack of consistency will kill any brewery, after all. After a few years and a lot of studying and learning and hiring good people, Maytag introduced four other styles of beer: a pale ale, a porter, a barleywine and a small beer. And this might not seem like a big deal but this is like 1975 when he does it, when finding American beer that wasn’t a pale yellow Pilsner was a challenge. At the time, Anchor didn’t even make one of those. Steam beer, their signature, was an open-fermented amber lager. The name supposedly came from what looked like clouds of steam coming off the fermenting pools.

If you do any research into the history of craft brewing in the US, you read a lot about Anchor and Fritz Maytag. Not only did Fritz rebuild Anchor into a thriving regional brewery, he mentored a lot of people who were interested in brewing beer that wasn’t pale yellow Pilsner. It’s not an exaggeration to say that if you’ve ever enjoyed a hoppy ale or a creamy, chocolatey porter or a robust amber, you have Fritz Maytag and Anchor to thank for helping keep those brewing traditions alive in the 70’s, 80’s and 90’s.

These days, beers from regional breweries take up almost as much room in grocery store coolers as the big names do, and brew pubs are ubiquitous. I’ve even seen signs that the market is a little saturated right now, and smaller breweries are going out of business just as Anchor is, or they’re trying to introduce hard seltzers or find what the next big drink will be so they can keep the doors open.

And maybe another reason this happened to Anchor is because ownership changed. Fritz sold Anchor to an ownership group who then sold it to Sapporo, and it’s easy to fall into the whole “soulless corporate overlords who don’t value things” argument, but I really do think that’s part of it. Anchor survived in the years after Fritz bought it because he didn’t need it to make money. He didn’t have limitless resources to put into it, but he could afford to let it run at a small loss until he got the business re-established, and then he expanded it slowly and conservatively.

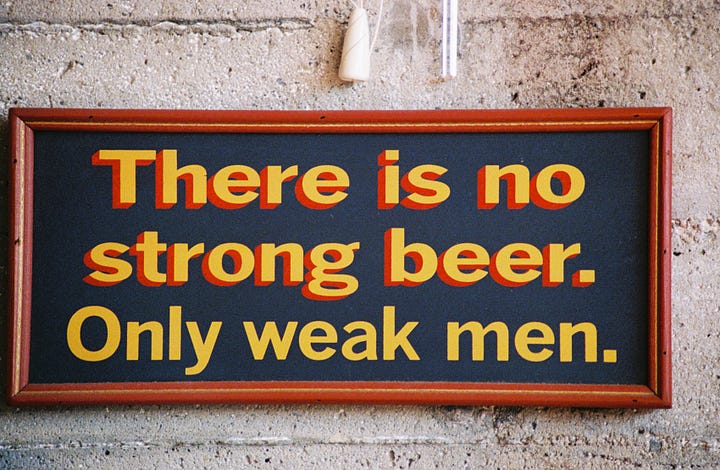

His approach also affected the tastes and styles of his beers. Every one of them was notable for its balance. Steam Beer had body and some light caramel notes and just a touch of hops. Liberty Ale was a subtle pale ale, with the crispness that came from using whole hops but that didn’t try to blow your palate out the way so many IPAs do now. The Porter was rich and creamy and chocolatey with just a hint of coffee. The one place he went wild was with the annual Christmas ale, which was a different recipe each year (a very closely guarded secret) but even then he started with the same base and fiddled with the secondary flavors.

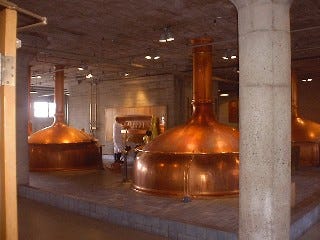

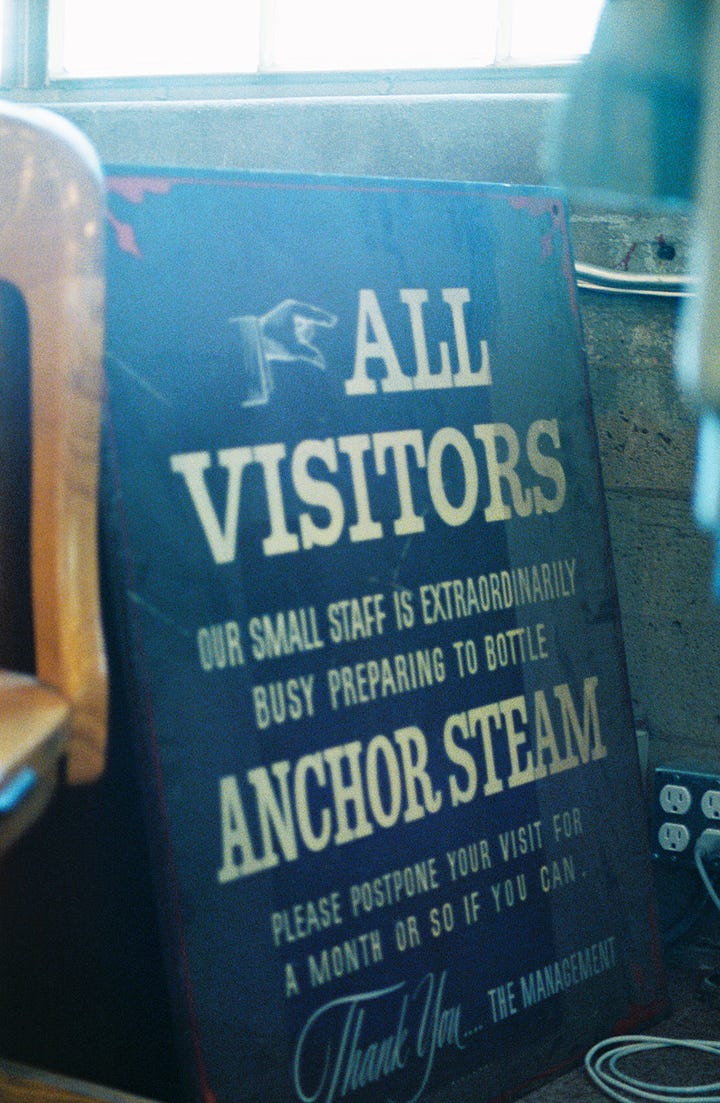

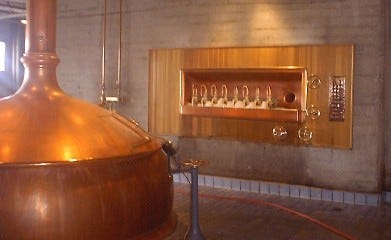

Fritz was involved with every aspect of the business, including interviewing everyone who worked there. That’s how Amy first met him, during the process of becoming the tour guide for the brewery. The tours were amazing. They started in the tap room, and then Amy led the group through every step of the process, from the brew kettle and mash tun, into the room where they stored the sacks of hop flowers, past the open fermenters with their waves and clouds of foam rising up, then down two floors to the conditioning tanks and filtration systems and back up to the bottling line and racking room, where usually we were just finishing up.

Yeah, a few months after Amy started, I got a job there too. Mostly I racked kegs and worked on the bottling line, and occasionally cleaned fermenters. It was a great job, one of the best I ever had in terms of just loving to work at a place. My fellow workers were a combination of old school San Franciscans who had other artistic and musical interests and just kind of fell into working there because it was the kind of place where you could make enough money to cover your bills and still have the mental space to chase your other interests. You could leave work and not think about it again until you showed up the next morning and started pulling kegs off the conveyer or loading boxes of empty bottles onto the line.

Something I think I’d forgotten before I dug out these old pictures was just how beautiful the place is/was. My memories are mostly of the people, but the place…these pictures don’t begin to do it justice.

And then there was the beer. Most days after the shift ended, we’d head down to the tap room where the tour was doing their tasting. Sometimes we’d do it before we’d even taken off our jumpsuits, making it easier for us to dip behind the bar to fill our own glasses with whatever we fancied that day. I mostly drank Steam Beer or Liberty Ale. They had substance but weren’t too heavy.

And then I’d walk a block to the bus stop, ride it over to Mission and switch to a southbound bus and ride home to my neighborhood, just past Joe’s Cable Car (Joe grinds his own fresh chuck daily) with the milkshakes of legend, past the Kingdom Hall of Jehovah’s Witnesses and the big retirement home, across from the Vietnamese place where I first had clay pot catfish and upstairs from the Fish Grotto and a Salvadoran place where I first ate pupusas. There were bodegas and taquerias and a reasonable pizza joint and some great spicy barbecue just over the hill in Visitacion Valley and if you heard someone speaking English it was probably a kid but there was no predicting what language you might hear. Businesses listed the languages spoken within, sometimes 5 deep: English, Spanish, Chinese, Tagalog, Vietnamese and more.

When Amy told me there was a job opening up, I applied and mentioned my experience pulling cases and driving a forklift in a grocery warehouse a decade earlier, mostly to show that even though my recent work experience involved being in front of a classroom, I knew my way around a factory floor. And during the interview, the people I’d be working with and directly under were interested in that. But not Fritz. He’d heard that I was a Stegner Fellow in poetry and wanted to ask me about that. He asked me what journals I read and said he had a subscription to The New Criterion (conservative in his literary tastes too) and mentioned that he’d studied literature at Stanford as well. He asked what I wrote about—roads mostly just then, having spent a lot of time on them criss-crossing the country and exploring the west—and who my influences were—Seamus Heaney at the moment—and then it was over.

I think I started the following week, though my memory is a little foggy on that. I do remember that I mostly worked in the racking room at first, rolling full kegs onto pallets, putting empties into the other end. It was physical work, and fairly solitary because the noise levels required we wear ear plugs and because Darek, who ran the line, was a friendly but quiet giant of a man. I lined up kegs on pallets and Darek stacked them with a forklift and drove them to the cooler. I loaded empties into the racket and Darek repaired kegs with busted valves. And at the end of the day, I swept up and scrubbed the floor and hosed it off and after clocking out, went up to the tap room for a beer.

It was a great job for an artist because it was work you could do without thinking about it. The bottling line was similar, though we rotated stations every thirty minutes because one of the jobs—watching for messed up labels—really was so boring that you’d fall asleep doing it. I carried a small notebook and pen in my jumpsuit pocket to scribble down lines that popped into my head while I was waiting for full cases of beer bottles to line up so I could palletize them. I’d chat with my co-workers: Rick, who ran the labeler and played pedal-steel with 3 or 4 local bands, all of them different genres of music; Thomas, a young guy going to SFCC part-time and playing sax when he could get gigs, writing and recording his own music, Kendra, who’d been the tour guide for so long she refused to do it anymore, who handled all the merch and desperately wanted to be a brewer (I think she eventually made that happen); Handsome Dan, an acting student at Bennington who came back during breaks to work on the line; and so on. Looking back on it, it’s hard to believe I only worked there a year.

We left San Francisco when the Stegner ended. We thought about trying to stay—Anchor offered Amy a full-time job and we maybe could have made the money work for a little while—but Amy missed Florida and family and it was my turn to follow her and to be very clear, the move was the right move and was wonderful and if anything I love Fort Lauderdale even more than The City.

Not long before I left, I tried writing a poem about beer, about the first brewers. I shared it with the Stegner workshop half-heartedly, not really believing in it as a poem, but it got a really positive response. I should try to find it. I printed off a copy of it along with a letter that I wrote to the people in the brewery when I left. Someone told me later that someone from the office had posted it on the bulletin board in the lunch room and without getting too precious about it, I feel like that might be one of my most artistic expressions ever. A poem written about the origins of a thing that happens at a place you belong to shared with the people in that place, with no intention of ever trying to make it into something bigger, something important or immortal. It’s just an attempt to marvel and wonder at something beautiful, something remarkable, and maybe share it with people who live it alongside you.

Okay, I found it, on the same old hard drive where I found the pictures I shared above. Here it is, untouched from when I abandoned it in 2005.

Reinheitsgebot

They didn’t even know that it was there—

the yeast flew wild on wind across the pools

of wort, malted barley-water thought blessed,

transformed by breath of God from water, hops

and barley into beer, a lesser Cana.

Reinheitsgebot attempts to keep it pure,

proscribing all but those three elements;

a formal pact for now five-hundred years.

The yeast is tame now, pitched on schedule,

and so the law is broken, except in spirit;

brewers stretch the limits to make it new,

slip in an herb or two, a nonce, a slant-

ed hint of seasoning, break tradition,

the occasional form.

When we moved to Des Moines, my first job was at a market just a few blocks down the hill from our house. I used the experience I’d gained, now six years in the past, to land a job selling wine and beer. We sold Anchor, in part because of its connection to Iowa. Newton, a small city not far from Des Moines, is home to the Maytag family. The appliance factories shut down a long time ago, and the Maytag family had sold them off before that happened, but the blue cheese is still made there and the name carries weight.

I’m sad that Anchor is disappearing, even a little surprised because I would have thought the name still carried enough cachet that some other brewer would at least buy the name and keep it going in some zombie-fied fashion. I’m kind of glad that’s not happening. I’d rather remember it, mourn it as it was than be disappointed in what it became.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed this piece or any of the work I’ve done here at Another Poem to Love, I’d appreciate it if you shared it around on whatever networks you’re maintaining these days. The content here will always be free. Do you have favorite poems or stories about disappearing places? I’d love to hear about them in the comments.

A tasty and refreshing piece; “a lesser Cana” is also very good. Fritz Maytag sounds like a character name in Vonnegut. That you were able to experience Anchor like that in its heyday is pretty neat.

I suppose many have written about the shift in where American trends originate, but you’ve got me thinking about that in the context of food and drink. A century ago, or maybe even sixty years ago, food trends often started in NYC, for example Nathan’s Famous hotdogs or General Tso’s chicken.

But by the 60s and 70s there was like a polarity switch or something to the West Coast, with mega changes to how and where beer is brewed (hoppy and local), influenced by Anchor and the English Campaign for Real Ale, coffee roasting with Peets and Starbucks, Alice Waters’ ideas, etc., accelerating into this century, a good example being the popularity of Huy Fong’s sriracha.

This is beautiful. I loved working there.

I might have more to say but I’ll need time.