There’s a scene early in The Lego Movie where our protagonist Emmet Brickowski is saying good morning to everyone and everything as he begins his day and heads to work. Along the way he meets Sherry Scratchen-Post and her many cats, and Emmet knows all their names, because of course he does. That’s the kind of person Emmet is.

I love how Emmet’s tone changes for Jeff, the last one in the line. This gag repeats in Lego Movie 2: The Second Part (the better of the two movies in my opinion, though both are fun watches), and because we have watched these movies eleventy-billion times, it’s become a running gag in our home as well. We even named one of our hens Jeff.

Jeff lays delicious eggs and likes to hop the fence and scratch around in the swale next to the street, which means we occasionally get frantic knocks at the door from passersby who are concerned that Jeff (or the 2-3 other hens who go wandering) will be hit by cars. We very much appreciate the knocks, for the record.

I’ve long associated the name Jeff (along with its many spelling variations) with an unwillingness to do what is expected of you. In junior high and high school, my best school friend (as opposed to church friend) was Geoffrey, kind of a misfit kid with an amazing imagination. He was my first writing buddy and my gateway into New Wave music and Prog Rock. He lent me his self-titled Violent Femmes cassette which I dubbed of course and told me about the one time you could hear music like that on the radio (the New Music Revue with Coyote J Calhoun on Sunday nights until it was canceled), unless the air was electric enough that you could catch the student radio station from Tulane which played Robyn Hitchcock and Black Flag and Siouxsie and the Banshees and R.E.M. and Echo and the Bunnymen. You get the picture.

He was a good enough writer that for our senior years while I was going to school half-days and preaching the other half, he was driving with a couple of other friends to the New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts to study writing. I was happy for him but also wished my vision for the future included doing something like that. I was waiting on Armageddon and the paradise to follow and there wasn’t much room for anything that didn’t include preaching or working. That would stay the same for the next 8 years or so.

We lost touch after high school. I’d had it in my head that once I graduated, my social circle would be limited to Jehovah’s Witnesses, so I didn’t really try to keep track of anyone. Many years later, when Facebook became a thing, I tried to look for him but no success. I heard from someone else that he’d gone to nursing school in California in the early 2000’s, but I never heard more.

In my high school years, I was religious even though I was torn between believing, wanting the rewards of being faithful, and also wanting to do all the things my non-Witness friends were doing. I wanted to drink, I wanted to do more than ache and burn for someone, I wanted to sneak out at night and ride to New Orleans to hear bands that were too cool to even stop in our little suburb for gas on the way to their shows. No one would have mistaken me for Christopher Smart is what I’m saying. I didn’t have that level of fervor.

But I’ve always found that kind of surrender fascinating, that need to give yourself over to something greater than yourself. For those who aren’t familiar with him, Christopher Smart was an 18th century English poet who was once confined to an asylum supposedly as a result of him praying loudly in public and begging people to pray with him. It’s also possible that he was committed because he owed some money, but whatever the reason, it’s during this commitment that most scholars believe Smart wrote “Jubilate Agno.” I’m only familiar really with a small part of this poem, the part that’s most often excerpted and anthologized, the part about his cat Jeoffry.

For I will consider my Cat Jeoffry.

For he is the servant of the Living God duly and daily serving him.

For at the first glance of the glory of God in the East he worships in his way.

And it continues in this form for like 70 more lines, each one beginning with “for” and making some statement about this cat. Smart switches between describing what Jeoffry does physically and how he praises God with his actions throughout the lines and what I love most about the poem is how sincere it feels, how innocent, even when he’s describing something that seems cruel.

For having consider'd God and himself he will consider his neighbour.

For if he meets another cat he will kiss her in kindness.

For when he takes his prey he plays with it to give it a chance.

For one mouse in seven escapes by his dallying.

For when his day's work is done his business more properly begins.

For he keeps the Lord's watch in the night against the adversary.

For he counteracts the powers of darkness by his electrical skin and glaring eyes.

For he counteracts the Devil, who is death, by brisking about the life.

Jeoffrey the cat tortures his prey but also protects all of us against what goes bump in the night. There’s so much in this poem and I encourage you to read the entire excerpt at the link above but also to check the entire poem. I have to move on, though, because what I want to talk about more than this poem is some of the poems it has inspired.

It can’t be a surprise that when you see a poem with such an unfamiliar form that you, as a writer, will want to try it yourself. I have—more on that later—and I love it when I come across one that I haven’t seen before. The idea for this piece hit me when I got my poem-a-day email from Knopf (you can sign up here if you like) on Sunday and saw this lovely poem from Patrick Phillips titled “Jubilate Civitas” which begins “I will consider a slice of pizza.” You’re goddamn right you will.

Phillips begins by describing both the ubiquity and the makers of a New York slice, line after line about the places they’re found and the people who make it, with every bit of the love and admiration that Smart had for his cat, but this is my favorite bit of the poem.

For time passes slowly awaiting a slice, and reminds us

how sweet it is to be alive at this moment on earth.

For it slides to a stop in a little city of shakers, where

with pepper and oregano, garlic and parmesan, we

citizens make it our own.

For you can fold it in half like a taco and eat it while

standing or driving, or walking and working your

phone.

For I have seen the bearded young men of Brooklyn

sit upright to eat it, riding bicycles through

redlights, at midnight, in the rain.

It’s the way Phillips invests so much meaning and emotion in this piece of food that is a part of the city’s personality because it’s so commonplace, because you can get it anywhere at anytime, because it never lets you down. There’s a line a little further down, the penultimate line, where Phillips says “For its commerce makes nobody rich and nobody poor” and that really sums up for me the title of the poem, “Jubilate Civitas” or rejoice in the people, the community. Sure, it’s possible to make gourmet pizza, but I feel like that misses the point of the food. Some foods are best because they’re sturdy, because they’re for everyone, and that’s what Phillips captures here.

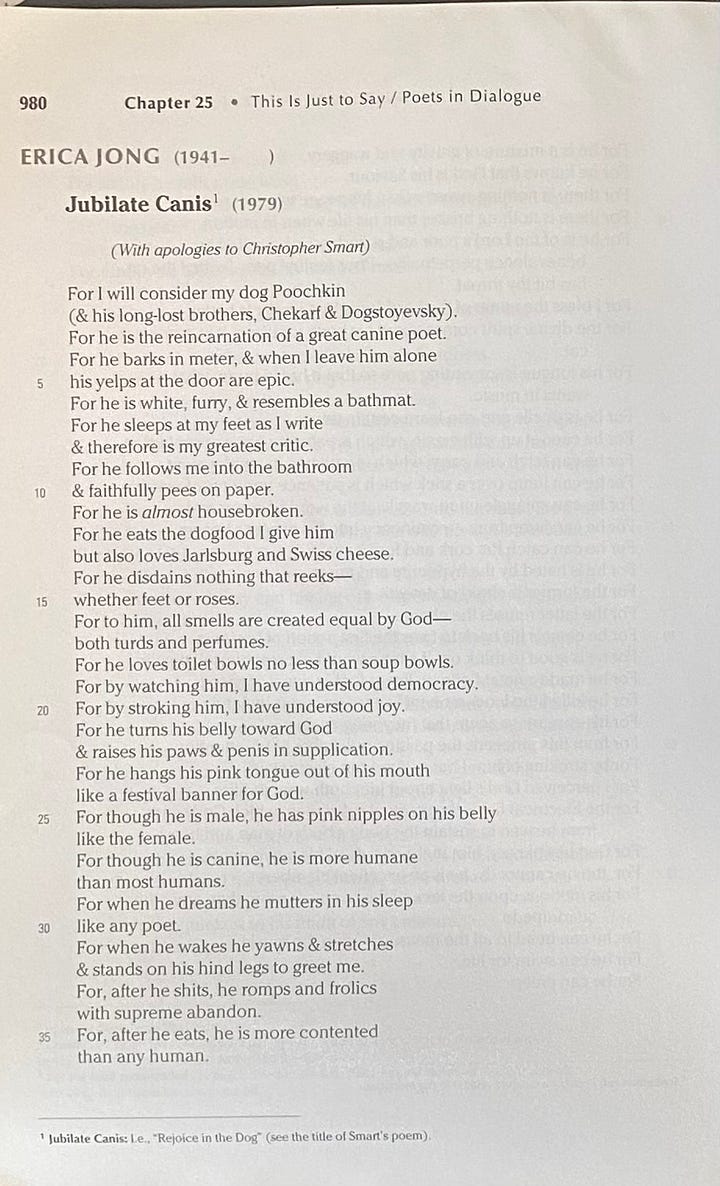

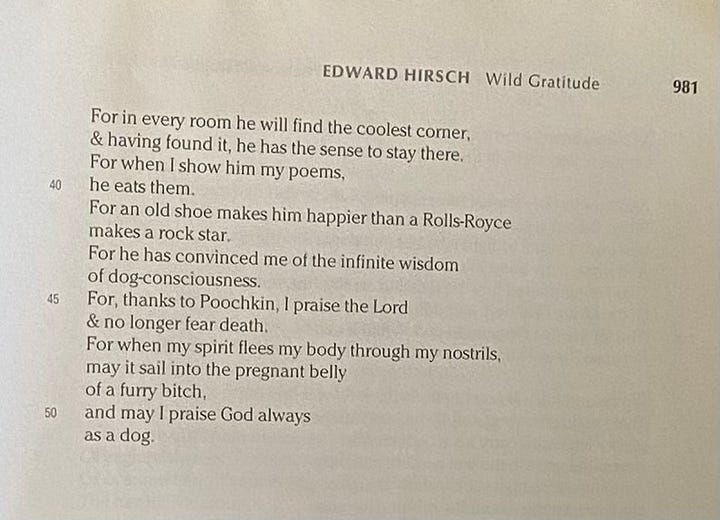

The first poem I ever saw that played with this form was in a textbook I used to use years ago when I taught at Florida Atlantic, by Erica Jong. It’s called “Jubilate Canis” and from what I can tell it was originally published in the Paris Review, which has it paywalled, so I took some pictures of it to share.

It’s not just that Jong writes about her dog, it’s that her dog is named Poochkin, and she’d previously had dogs named Chekarf and Dogstoyevsky because of course she did. Do I love this? Do I have a cat named Willa CatHair? Yes and yes. Here she is trying to take the idea of sitting in a box to a whole new level.

Jong goes more for the funny than the transcendent in most of the poem, but I really like the way she closes it.

For when my spirit flees my body through my nostrils,

may it sail into the pregnant body

of a furry bitch,

and may I praise God always

as a dog.

I think the key to writing a poem like this is that you want to do more than just copy the form. You want to honor it in some way without strictly echoing it. Phillips gets at the deep humanity Smart was trying to describe in his relationship with Jeoffry and Jong reaches for that sense of eternity and oneness with another being.

I thought about going into Ed Hirsch’s poem “Wild Gratitude” because he mentions and even quotes from “Jubilate Agno” in it, but I think I’m just going to link it because I’m more interested in the poems that use Smart’s form and also I promised earlier that I’d talk about my own try at it.

It’s about my dad. I titled it “Jubilate Patro,” and while I’m not usually one to give long biographical notes about a poem before I read it to an audience, this is kind of an exception. If you’ve read my earlier posts, you know that my relationship with my parents is/was kind of fraught. My dad was an elder with the Jehovah’s Witnesses for most of my life. It was a fundamental part of who he was, but it wasn’t something he could do all on his own. It was a family affair.

See, one of the requirements to be an elder was that your family had to be good examples for the congregation. If your kids fucked up, it was a sign that you needed to step back from leading the congregation in order to get your own house in order, so my dad’s position was dependent on my sister and me playing the part. And I want to be clear, at this time I was a full-on believer. My doubts about the faith didn’t creep in until I was in my mid-20’s. The parts of me that were twisted up were, let’s say, carnally-motivated. I was a teenager. But a big part of what kept me from fully giving into those desires was the knowledge that my actions could cost my dad one of the things that mattered most to him.

This stuck with me so much that when I decided to leave the church when I was 26, I tried to do it quietly. I just stopped going, tried to disappear, because so long as I was just what they call “inactive,” no shame would come upon my father. Not that he’d have lost his position over me wilding out at that point, but it’s a tight community and he’d have been embarrassed and I didn’t want to cause him any unnecessary pain.

That strategy didn’t work. I mean, Hammond is a small town and I was working in a restaurant and a bar and going to college and inevitably someone saw something and reported me and there I am answering my front door a couple of days before Christmas very tired and slightly hung over and there are two elders asking me if I wanted to come meet with them about some stuff they’d heard I was doing and I told them no and a couple of days later they called me and told me I was going to be disfellowshipped and I hung up on them.

If you’re disfellowshipped from the Jehovah’s Witnesses, any members of your family who are still Witnesses are supposed to cut off all communication except what’s absolutely necessary. The idea is that the desire to be close to your family again will cause you to repent and come back to the faith. I’m not going to get into the numerous ways in which that’s messed up right now, because this thing has already gone longer than I planned and that’s a whole essay of its own, but suffice to say whatever closeness I had with my parents ended the night I told them I’d been disfellowshipped and wasn’t planning to come back.

But still, he’s my dad you know? And some years later, around 2009, I wrote this poem. It’s in my book, A Witness in Exile, published in 2011 by Louisiana Literature Press. I have copies in my closet I’d be happy to sign and send out. In the poem I tried to lean into the form hard, and I call my dad by his first name because that’s what I called him growing up. That’s a whole other story too. Okay, enough delaying.

For I will consider my father Sam

For he praises God in his mumbles and circular stories

For his left arm is crooked to remind him of original sin

For half his brain was cut off from blood when he was a baby

For it rewired itself

For his right arm is mighty in exchange

For with it he did not spare the rod

For he was an elder until Alzheimer’s took away his memory

For he was an accountant until Alzheimer’s took away his memory

For he praised God in his mumbles and circular stories before Alzheimer’s took his memory and thus it is a part of his soul

For he is still a storyteller even though he gets lost in his stories sometimes

Two things. My dad had a different form of dementia than Alzheimer’s but I didn’t remember what it was called and I couldn’t exactly ask my mom for details. And the last time I talked to him was about a week before he died. My sister told me he was fading and that this would be my last chance, so I called and we talked and it was good. It was enough. It wasn’t enough but it was what I could get.

For he made me hold a nail while he hit it with a hammer and so taught me trust

For I learned to drive a nail myself at 7

For he drove a dump truck with one good arm and so taught me that while I may be able to do all things, some times I should not

This is much later in the poem and I want to emphasize that all of it is true. I will add in that we lived in a trailer with wood paneling walls and so on the occasions when we were driving nails into them, they had a tendency to jump and rebound and buddy let me tell you that’s an experience when you’re the one holding the nail.

When my dad died, I posted part of this poem on my website as a memorial of sorts. I ended with the line “For I will never know a man greater than him.” Don’t go looking for that website by the way. We forgot to re-up the domain a little while back and now it hosts Asian porn. Anyway the elder who conducted the funeral mentioned the poem and I felt a little guilty because this is how the poem ends.

For he went to his father’s bedside when it was time for him to die

For he stayed a month and helped build the coffin

For he would not let the funeral be held in a Kingdom Hall in order to protect the body of the church

For he taught me there are things more important than family and sometimes I hate him for that

For his father is Jehovah and he has no son anymore

I didn’t post this part of the poem on my website after he died. Of course I didn’t. But this is who he was. He was a good man in some ways and unbending in others and that caused me no end of pain at times. I could not be the person I am without him but I also wish I could have been enough for him as I was, as I became.

Thank you for sticking with me this long. Do you know of other poems in this form, or have you written one yourself? I’d love to read them or about them. Let’s talk in the comments or over in Notes.

This is such an inspiring essay; thank you for it. I'm a poetry beginner so had never heard of Jubilate Agno or the many poems it has inspired. They are beautiful and funny and profound. I will think of that line about the bearded men of Brooklyn next time I grab a slice, for sure.

Sorry to hear about your father, too, Brian. Some beautiful lessons and memories in there, in the midst of the complicated and difficult. It can't have been easy to write but it's beautiful to read.

Thank you for writing this Brian. Of course I already know this story -- I have lived through half of it with you. You are strong and beautiful and you could not be that without him, and yet he made you be without him for so long... to me, this is the why, of poetry.