Reclamation Part 4

This is the fourth installment about my multi-section poem responding to Robert Frost's "The Gift Outright." Here's a link to parts 1, 2 and 3.

When I was young, the world felt impossibly small to me, but simultaneously too large to fathom. By young I mean the time when this poem takes place, so high school, junior year. I’m in Slidell, the New Orleans suburb of about 30,000 people I’d guess, which was the biggest on the North Shore but that’s a low bar to clear. I can’t say I knew every inch of it but between the door-to-door preaching I’d done since I’d moved there in 5th grade and the pizzas I’d delivered in my 1978 baby blue Honda Accord (only lemon they ever made—look up constant velocity joints sometime), I was close. That was my world, one I would leave pretty quickly after graduation.

The wider world was New Orleans, which I went to rarely. It was bridges and bridges away, the kind of place I could get lost in and I didn’t like being lost. It was also full of sin which scared me because I wanted it so much and I knew it. The elders in our congregation, my dad among them, would tell us that the danger of sin was that you’d accidentally get close and be sucked in like quicksand,* but my problem was that I knew I wanted to dive face-first into it and I still believed too hard in the promise of everlasting life in paradise to chance it.

And honestly, that was kind of the extent of my world. I’d been other places, for vacations, for Jehovah’s Witnesses conventions. I’d been to Brooklyn to visit the world headquarters (of which there is no sign any longer). I’d read about other places, voraciously in some cases, but they weren’t real to me the way the corner store at Cousin and Front St with the Defender video game and the quarter juice plastic bottles shaped vaguely like hand grenades was real. Not real like the grass in front of the Bud’s Broiler on Sgt Alfred where I rolled around after bouncing my bike over the hood of a car on my way to sign up for summer school Driver’s Ed.

That’s an unfair comparison, of course. The place you live will always be more real to you than any place you imagine, but the wider world was also distant to me because I never really had any hope of experiencing it. We were never going to travel overseas—by this point my dad had already traded his full-time job for a part-time one to become a full-time volunteer preacher and my mom was about to do the same, so money was tight again, but also they never seemed to have much interest in doing it.

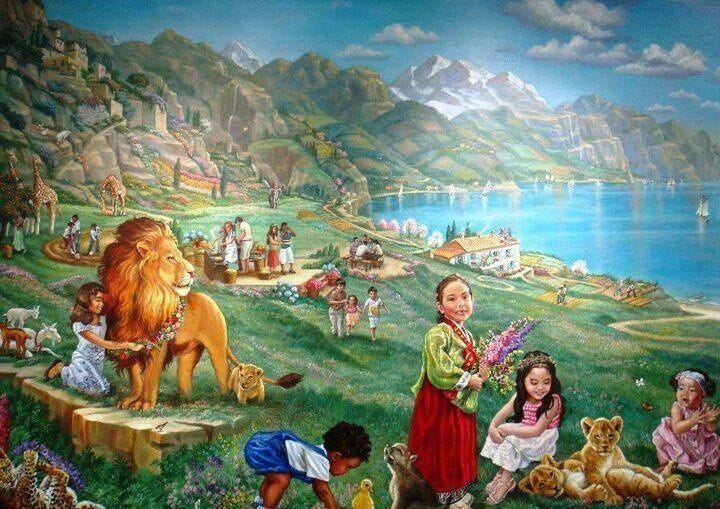

Even if my family had gone, what would we have done? Every part of our lives was lived through the lens of being a Jehovah’s Witness. We’d have toured the local branch office of whatever country we were in, gone to meetings there, talked with these people we’d met about how amazing it was that we truly were an international brother and sisterhood. Maybe we’d have gone to a museum, or a castle, but even there we’d have made snide remarks to each other about the religious iconography and how wrong their beliefs were. When your whole personality is built around the belief that you and only you know the TRUTH about the Bible and Christianity, you’re pretty insufferable. Besides, there’d be plenty of time to go there after Armageddon when we’d restored the entire earth to paradise conditions and then we wouldn’t have to deal with all that worldly stuff.

Still, I was in high school, with all the angst and emotion that brings, and I saw my school friends rebelling in ways large and small and I desperately wanted to rebel with them. I did in small ways when I was around them. I shoplifted porn from any number of convenience stores, cursed an unnecessary amount, as though I thought if I did it twice as much at school then it would be out of my system and I wouldn’t do it at home (that mostly worked), I hit on girls who weren’t Witnesses very unsuccessfully, drank when I could get an adult to buy it for me. Normal stuff.

And I wrote. That might have been my greatest sin. It was my favorite one.

I mostly wrote poems, the kind you expect an angsty high-school boy who reads Cummings and Baudelaire and listens to prog rock and new wave and this new music called hip-hop and soul and top 40 and anything that either gets played on the radio or that you can buy for $2 from the remaindered bin at the record store to write. I wrote stories also, mostly copies of stories I’d read in other places with marginal changes (plagiarized, let’s be honest). I stole dialogue from Watchmen for one, I remember. I thought I was slick. (I was not slick). But this is how we learn.

I sat in the back of my classrooms because it was easier to hide that I was mostly either reading something other than what was being discussed or writing something not connected to class. Also, it was closer to the windows and if our high school had air conditioning, it was not effective. Not that there was ever much of a breeze coming off Lake Pontchartrain unless there was a storm coming in which meant you soaked up as much of that chill that preceded the heavens opening up because the windows were closed tight against the torrents.

That’s when this section of the poem takes place. Junior year US history, spring term, 1986 I guess. It had to be the spring because we were reading about the Civil War, aka The War Between the States to most of the school faculty, the War of Northern Aggression to one of them. There’s a poem by Natasha Trethewey called “Southern History.” Pretty much that, only I was a white dude in the classroom so I didn’t have near the same experience or reaction to it as she did. Which is what I’m kind of getting at starting in my third line when I say “We didn’t care what happened / In Massachusetts, in Virginia.” It was words on a page to me, words I needed to be able to identify on a test in a couple of weeks, and I could do that easy.

What mattered to me and the non-Witness friends I had at school was what we wrote, what we listened to, the tapes we swapped and copied. And we had to get music that way because the radio stations we picked up were just the big ones and the record stores were mostly in malls and department stores and would never carry anything punk or new wave unless it was radio-friendly so forget Black Flag or Violent Femmes or Siouxsie and the Banshees or Robyn Hitchcock or The Smiths. On a stormy night, if there was just enough electricity in the air, we could sometimes pick up the college radio stations from Tulane. And for a brief glorious moment there was a Sunday night show on WQUE called the New Music Revue with Coyote J Calhoun. We wanted to pour those emotions onto paper and share them with each other but only with each other.

Some of our teachers knew we wrote and they encouraged us. They got us involved in the school literary magazine. I got to be an editor for the parish lit mag too. And we submitted and published poems and stories in those places but never the stuff we wrote for each other. That was ours. I gave the magazine the poems that fit the persona I wanted to be, that I wanted the audience to see.

I guess I hoped they’d see me as something other than what they saw every day. I know I wanted to be something other than that, but I didn’t know how. I just knew how to be conflicted, how to wear the face that fit in with the people I was around.

Here’s section 4 of Reclamation:

That fall we studied US history

in sweaty Slidell classrooms, south-facing

sunny windows. We didn't care what happened

in Massachusetts, in Virginia,

not really even in New Orleans across

the lake which sent dark clouds each afternoon,

thickened the air to roux. Bolded names and battles

told us what to study should we

decide it mattered more than writing our fears

in secret notebooks we'd swap at lunch

sure that no one in the world had felt

this way before, not even Morrissey;

maybe Robert Smith and Siouxsie Sioux

who we only ever heard on stormy nights

when the air was electric, boosted WTUL

to radios we hid beneath our pillows.Thanks as always for reading. I had a harder time approaching this section than I thought I would, and then work ramped up and I made excuses and crocheted a lot and let the not-writing take over me. Then on Thursday I went with my kids on a school trip to a performance at the Civic Center of a play/dance based on the book What Do You Do With an Idea?” by Kobi Yamada and I was invigorated and I’m going to try to ride this feeling for as long as I can, work be damned. If the show comes to your area, go see it.

*There’s a joke about GenX believing quicksand would be a much larger part of our lives because of tv but that really is the metaphor they used.

I enjoyed this so much. I'm glad you eventually found a way to get it written.