Back in August I had the chance to take a one-week class in filmmaking, the first one I’ve ever done. The constraints were that the film had to be 3 minutes long, not including credits, and had to have something to do with climate change. My partner and I wound up with a story about a woman who underestimates the seriousness of some nearby flooding and by the time she’s ready to evacuate, she’s unable to do it on her own. It’s done as one half of a phone conversation, and the video is footage from news stories about floods. It ends with her leaving her home in the back of a National Guard truck with her cat and only the things in the one bag she had already packed.

Personally, I’ve never run from a storm. That’s not meant as a brag. Most of the 36 total years I lived in hurricane country I never needed to run. When I was a kid, hurricane days off school were more likely to be beautiful than stormy. It seemed like the storms always turned east and hit Biloxi or Mobile or Gulf Shores. But also, the storms just didn’t feel as dangerous. The ones the adults all talked about in hushed whispers, Camille, Betsy, they were the outliers. There was one storm, Elena I believe, where my parents took us in the middle of the night from our trailer to the house of some friends from the congregation across town, but the next morning we went home, and apart from some water in the streets, nothing seemed amiss.

The only scary hurricane I’ve never ridden out was Wilma. This was the same year as Katrina, which in Fort Lauderdale came through as a category one that did plenty but was a baby compared to what it became. Wilma was a fading category two when it hit us, but the eye was 70 miles wide and the storm bands pretty much covered the state. We lived in an old Florida apartment, low to the ground, walls made of cinder blocks and rebar, with hurricane shutters and strong doors. We thought about leaving, but where would we go? With regular traffic, it’s a ten hour drive to Georgia and we didn’t know anyone there we could have stayed with. We didn’t have the money for an extended hotel stay, not for three humans and two cats at gale force wind prices.

We hunkered down, got supplies, put blankets on the floor of the most secure interior closet we had in case we actually were going to try to sleep. The rains came and the winds picked up. Every once in a while I’d ease the door open to see what it was like outside. The wind bowed the palm trees and I thought about Victor Hernandez Cruz’s poem “Problems With Hurricanes” and the lines “How would your family / feel if they had to tell / The generations that you / got killed by a flying / Banana.” I shut the door. I thought about the one person killed during Hurricane Charley, a guy who stepped outside while in the calming eye of the storm to have a smoke only to have a tree fall on him. The winds calmed and I looked out. The table on our porch had come over the fence and wedged itself between my car and Amy’s truck. The winds picked up, blew directly at us, and then the water was coming in under the door, and we were mopping it up with towels and trying to push it back.

We did this in dim light. The electricity had been out for hours and the hurricane shutters kept out whatever light was available outside. I don’t remember being afraid, really, in the moment. I had confidence the house would hold—it had been built in the 1950’s and what it lacked in glamor it made up for in solidity. But the roof could have come off or a tree could have been hurled through the wall. After the storm passed, when we walked though the neighborhood, we saw a row of parked cars all with the windows smashed out and coconut sized dents in the fenders. In the park, an old fighter jet on a pedestal was now nose-first in the ground. We came out of it fine. We were lucky.

I thought about all of this when I was trying to come up with something to write for that filmmaking workshop, something that could maybe help people who’d never faced it understand why people might stay in the face of such a storm, why maybe they wouldn’t have a choice. But more than that, I wanted to think about what to take with you when you leave a place with the thought that it might be a while before you come back. That you might never come back except to visit. That you might never come back at all.

Like I said, I’ve never run from a storm. Never had to. But there have been plenty of times in my life when I couldn’t run when a storm was coming, where I felt blessed that the storm turned, guilty as I felt about that for the people it hit. There but for the grace, you know?

I know a little something about leaving a place, though, so I tried to lean into that. I know about making choices on what I can take and what has to stay behind. I don’t know what it’s like to move to a place where I don’t have something waiting. That’s fucking terrifying to me, the idea of just showing up with what I could carry and thinking “guess I’m here now.” I’ve got pretty much every advantage I could want in this society and that idea just knocks me to my knees. Think about that when you see posters online or talking heads on TV blithely suggest that people should just move out of danger areas. Look at the way one of our major political parties is demonizing people who relocate from dangerous spots and then imagine you have to do it.

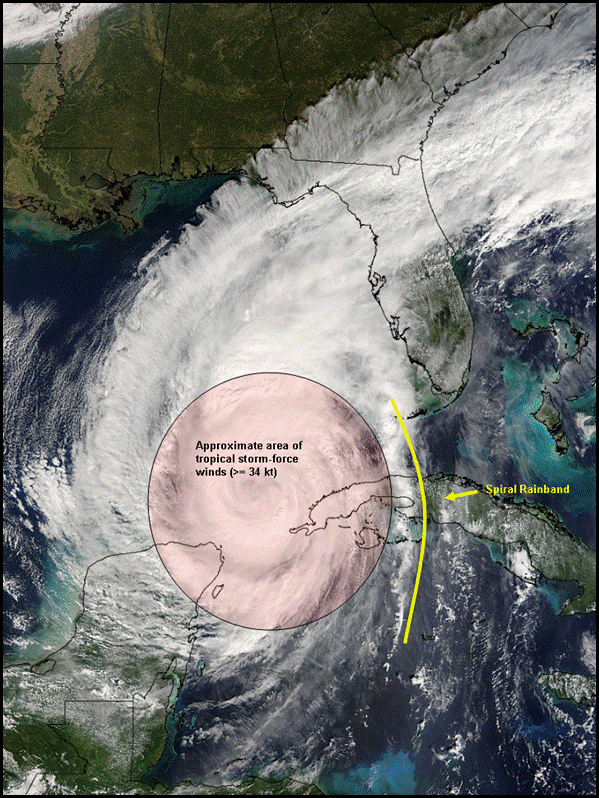

What I wrote first for this film project was kind of a poem. I imagined speak/singing it maybe over video of hurricanes, satellite images, storm surge, destruction. I haven’t touched it much since that initial burst of writing. I didn’t think I would share it with anyone so it’s still pretty uncooked. But I want to think about it some more, given this latest storm and the folks trying to dig out of it, find their people, figure out what they have left to rebuild a life from either where they are now or where they’re from.

So You Want to Run From a Storm: A Checklist

Must Have:

People you can drive to with a floor you can sleep on

Or

A credit card with room on it and a hotel with space (there won’t be any hotel rooms)

A car that’ll get you there and back

Next month’s rent

The first book you ever bought with your own money

A boss who don’t expect you to open up for him because he flew with his family to Atlanta just in case the storm don’t turn and he’s depending on you

Gas money

Three days of clothes

The smell of buttermilk biscuits right out of the oven

All the water left in the store, even Dasani (there’s no water left in the store)

Jumper cables and a can of fix-a-flat

Toilet paper

Mom’s old road atlas for when the phone dies

Chargers for if there’s power wherever you wind up and an outlet no one will bust your ass over

Every recipe you ever learned

Every battery you can steal

Copies of your résumé—you might be there a while

Your best pillows

A gun if you got one but don’t tell no one else in the car about it

All the ice left in the store (there’s no ice left in the store)

Your good crochet hooks and all the yarn you can stuff in a bag

Headphones

The voices of your neighbors cussing each other in the front yard

A small bag of crushed oyster shell from the driveway, to guide you back home

A flatboat to get you the last mile

Thank you as always for reading. Tell me, what goes on your list? What do you take with you?

P.S. About the film. It came out okay. I haven’t been able to get a copy of it from my partner. He keeps putting me off, which is fine honestly. The important thing was the experience. I’ve since downloaded the program he used to put it together, DaVinci Resolve. I haven’t played with it yet, but the app button looks at me insistently, so maybe.

Beautiful - thank you, Brian.

If you do end up turning it into a poetry film, feel free to drop us a line at movingpoems.com where we're always looking for new poetry videos to share.