One of the first poems I ever published, way back when I was in high school, was about photographs. That might have been the title. I don’t exactly remember and fortunately for me, that poem has been lost to the passing of time. (Young people will never know how wonderful it can be to just let parts of their history be mysterious rather than recorded for posterity.)

I do remember that the poem was about the photos I carried in my wallet (remember that?), but unlike the adults in my life, the pictures I carried weren’t of family, of grandparents or cousins, though I might have had a picture of my sister in there? The few I had were of classmates, school pictures, and even then they weren’t of the people I was actually friends with, because why would I need a picture of them? The more I think about it, the only picture I definitely remember having in my wallet was of this girl who sat next to me in French class. She was a cheerleader, and I let her look off my paper during vocabulary tests, and she gave me one of her school pictures in return. That detail made it into the poem as well.

I remember the poem had a sneering tone to it. I definitely used the word bullshit in it, though I’m sure the St. Tammany Parish Literary Magazine where it was published censored it. “A collage of unhumans” was also in there and something about how I was constantly sitting on them. Looking back, it’s clear I understood there was something kind of sad about being a kid who was trying to do this adult-like thing—carry around photos of people who mattered to you, so you could show them to your peers, or be reminded of them when you went to pay for something, like the water bill or a new typewriter—but who had to get pictures from people who needed something from him so he could lie about the relationship he had with them to his co-workers at the local chicken joint. But not lie too much, because he went to church with some of those co-workers and he couldn’t risk word of it getting back to his parents.

There were pictures I cared about though. I was a photographer for the yearbook for a couple of years, and I was great at it in the sense that I was obnoxious and would shoot anything anywhere. I discovered early on that the camera was a ticket to get into places I would have otherwise been shut out of. I stopped being Brian, loudmouth Jehovah’s Witness, and became the camera guy. It changed me as well, because I also learned pretty early that the best pictures I took were candid shots, but you only got candid shots when everyone forgot you were there, which meant I had to not talk.

I still take pictures but I don’t think of myself as a photographer. I never did, even when I was using a SLR and shooting film, but especially not now when all the pictures I take are with my phone. These days I’m not trying to get into places where I’m not welcome and I’m definitely not worried about taking the last picture on the roll of film because I’m afraid I’ll miss a better shot. Getting rid of the scarcity of the photograph has unquestionably changed my relationship to it.

Which is not to suggest that I value photographs less now than I once did. It’s just different. When I was a kid, a fundamental part of every visit to my grandmothers’ houses was the pulling out of the photo albums, both to revisit who my cousins and aunts and uncles and further-outs had been and to see who and what had happened since my last trip through the images. The reactions were some combination of “oh my god is that you” and “I don’t recognize this person” and “where did you take this” and usually the answers would run into a story and sometimes they’d be ignored and pushed past and sometimes whoever was taking me through the photo album would peel back the plastic and pull the photo away from the page and see if there was any writing on the back of it. And if we were lucky, there was some hard-to-read cursive with names and place and date on the back. And if not, then maybe we would ask around to someone who was in the next room, or think we would come back to it later and then move on.

For years now, my personal version of that has been the photo library on my phone. Currently I have almost 11,000 pictures on it dating back over 8 years. Some of those are memes I’ve saved or screenshots, detritus of a life spent too much online. But most of them are pictures of people and places and moments. On occasion my daughters want to look at them and then they ask me the questions I asked when I was looking at photo albums as a kid and I give them the same answers I got back then.

Earlier this year, Amy asked me for one of those digital picture frames, one that lets you upload images to the cloud and then it shows them on an endless slide show. It sits on a sideboard in our dining room and sometimes when I’m sitting at the table, I’ll find myself getting lost in the pictures, seeing my daughters as babies and toddlers, thousands of pictures there probably given that both Amy and I have dumped large parts of our libraries into it.

But just like those earlier photo albums, there’s nothing in the picture itself to provide context or explanation. That’s all in my head, which means it could be—will be one day, more than likely—lost, especially the pictures from before the girls were old enough to start remembering their specific experiences.

There’s been a lot of study about how technology affects human memory, and we’ve all seen it firsthand. Ask people of my generation or older about the need to memorize phone numbers and they might be able to rattle off not only the number they grew up with but all their best friends’ numbers too, but they can’t remember their friends’ numbers now. Why is that? Because they don’t have to anymore. All those numbers are in their own phone’s memory and the brain knows that so it offloads those things and uses those resources for other stuff.

We’ve known about this as regards photographs since well before the digital age but there’s no question in my mind that we do it more now just because pictures are so easy to take now. When I was a kid taking pictures on vacation, my parents would buy my sister and me a couple of rolls of film with the warning that they weren’t going to buy us more so make it last. That usually meant I spent the last two days wherever we were with one or two pictures left on the roll saving it for the right time which of course never came. Now I take pictures of lots of things with the idea that I can just delete anything that didn’t come out the way I wanted it to, because it’s not like I’m going to run out of memory.

Lately, though, I’ve been dialing it back a little. There’s a scene in The Mitchells vs the Machines where Rick, the technophobic dad, is trying to get his daughter Katie to stop experiencing everything through the lens of her phone and he says “your eyes are nature’s camera.” I say this to my kids when they want to take a picture with my phone, and then I give them my phone anyway because they do the eyeroll so well in response. And it’s true that Rick is a little too anti-technology for the world he lives in but it’s also true that there’s value in just being in the moment. I don’t have to document every thing I do, and I really don’t have to share it with the world (but that’s a rant for another day) but even if I thought I had to, the fact is that there’s only so much context I could provide for any picture I take, and that at some point the people who could understand that context will be gone and those stories with them.

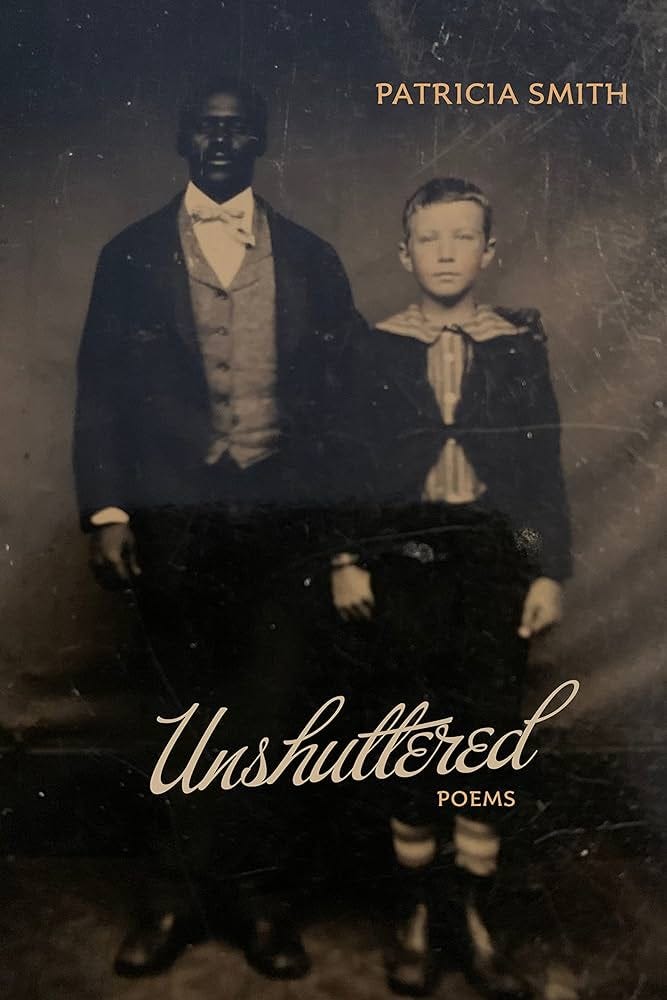

Patricia Smith comes up against those missing stories in her latest book, Unshuttered, which came out this past February from Northwestern University Press. It’s a phenomenal book, because of course it is—it’s Patricia Smith. Here’s a quote from the Preface:

These images—each captured between 120 and 180 years ago—represent a time when former slaves learned to redefine the word “home,” and even those born after Emancipation struggled to redefine the word “free.” Only a few of the images have a name scrawled in pencil on the back. Often, it is only a first name. Sometimes the full name is given or the location of the studio is identified, but rarely is there anything more.

Confined within the stifling boundaries of the photographs, these men, women and children peer at us from the past. They cannot laugh, weep, speak, or scream.

They are wraiths, their stories growing dim.

Smith continues in the preface to talk about how she identifies with the people in these pictures that she has collected over the years. She talks about her mother who moved to Chicago during the Great Migration and who wished to separate herself from her upbringing. “The only hint of her past was a battered suitcase full of faded Polaroids of people she refused to identify.” But the people in these photographs, both her mother’s Polaroids and in the ones she collected, had stories and those stories have disappeared

.

So Smith wrote new ones for them. And the poems in this book are those stories. There are 42 poems paired with images, and then the title poem which closes the collection and the voices really range. There’s a formality to all the voices but the images lend themselves to that given that having a portrait made during the time frame when these were taken was an expensive proposition.

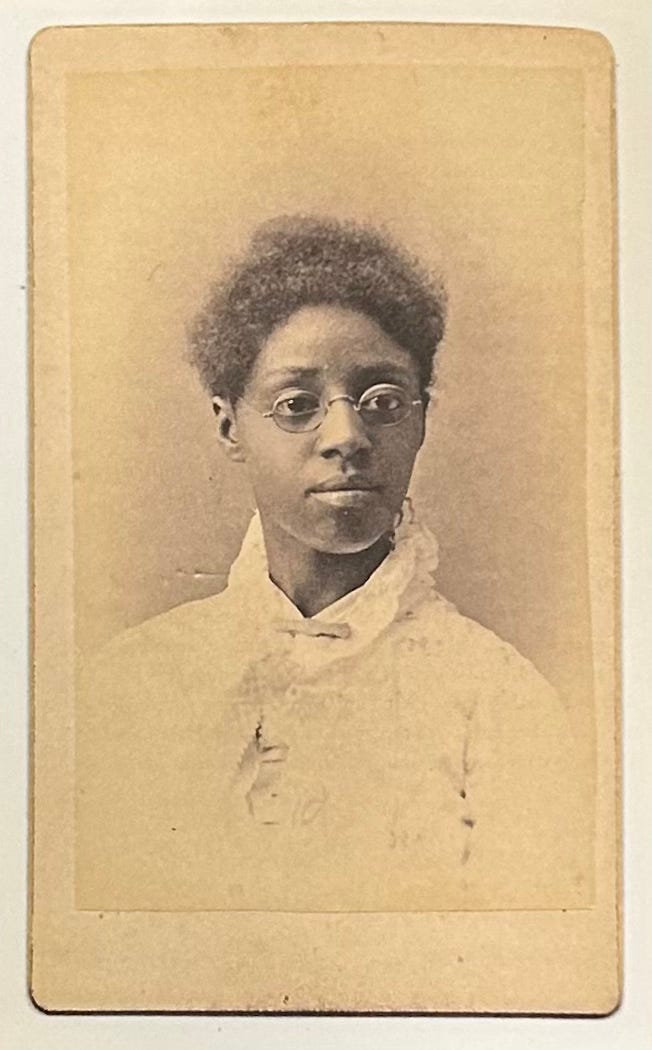

The one I want to focus on is number 16. It begins

Conjuring a woman is maddening. Such feeble guarantees.

I dare first what is needed—the store-bought blouse, its

treasured frill and stiff curl of cotton. The bogus bar of gold

greening at my throat.

I love the way Smith works the tension in here from multiple angles. The opening suggests (and we’ll get confirmation soon) that the speaker here is presenting as a woman and that the photograph is a way of making it palpable, concrete. But there’s also the tension about whether or not the speaker has the resources to pull it off, “the bogus bar of gold / greening” is just a marvelous image.

The nervousness of the moment really comes through in the next lines:

I dare sugar in practiced poses while

three overlooked hairs waggle on my chin and light struggles

through these flawed hillsides of hair—hair oiled heavy

and patted toward a quite uncertain she. What a weak

and reckless way to step forward—sitting on my hands

to quiet their roped veins and ungirled work, hiding blunt

mannish nails, bitten just this morning to a troubled blood.

The anxiety in these lines is so powerful to me, the nervousness in her voice, her feeling that everyone will obviously see through her appearance and being so nervous that she’s bitten her nails down to the quick. I used to do that when I was a child and I can feel the stinging in my fingertips as I type this.

You can’t see in the photograph that the speaker is sitting on her hands, nor can you see her feet, described later as “thick toes, accustomed to field” that are squeezed painfully into borrowed shoes. And the face gives no evidence of physical pain, but that makes the speaker even more believable. She has prepared for this moment, this unveiling, and nervous as she is, she will not allow something as minor as discomfort to ruin it.

Smith turns the poem in the second stanza by changing the verb tense, moving into second person, though it feels more like the speaker is talking to the picture or into a mirror rather than talking directly to the reader. It’s a fantastic use of the second person, because usually the effect of the move is to grab the reader by the shirt, so to speak, and demand their attention, but here it’s more introspective.

Tell me that I have earned at least this much woman. Tell me

that this day is worth all the nights I wished the muscle

of myself away.

The “tell me” is a request for validation or acceptance, but again, the speaker isn’t asking for it from us. She’s asking it from herself, which is important because she isn’t sure that she’ll receive it from anyone else. The end of the poem leaves this uncertain:

Here I am, Mama, vexing your savior,

barely alive beneath face powder and wild prayer. Here I am,

both your daughter and your son, stinking of violet water.

The “vexing your savior” combined with “wild prayer” really hits hard for me because of my own experiences of estrangement from family over matters of faith. I feel what’s at stake and why she still needs to be this person no matter the cost. There’s an ache here that stays unresolved, and I think that’s why it sticks with me.

Thanks as always for reading. I haven’t posted in a while but I hope to get back onto a semi-regular schedule soon. I certainly have enough poems to write about.

Do you have stories about photographs of your own? I’d love to hear them.

Wonderful meditation on photography. I think you’ve really gotten at some of the aspects of old photographs, which seem to have a magic about them that modern cellphone photos lack. Perhaps it has a lot to do with the vagaries of older technologies, or the tactile nature of handling a tiny snapshot, the writing on the back, sometimes bleeding through to the image.

And then there’s how almost all photographs from the 19th century are posed, shot in a studio, with the subjects wearing their best clothes, even cowboys and loggers would dress up, giving them a formality and gravity that contrasts strongly with today’s dominant “candid” ethos. Also, those studio portraits really represent the photographer’s point of view, whereas today it’s the subject who is often “acting” for the camera.

Does Smith’s book include any persona poems where the speaker is the photographer, the other half of the dialogue?