I admit, I’ve had a hard time of it the last month or so. This is usually my favorite holiday season, Mardi Gras, and even though I’ve lived far away from it this century, I’ve kind of worked around that by listening to copious amounts of music (thank you Gambit’s Big Mardi Gras Playlist, watching parades on YouTube (especially the Intergalactic Krewe of Chewbacchus, which I want to see in person someday), and sporting my utterly ridiculous Half Assed Walking Club scarf in purple, green and gold. It’s like 11-feet long. I didn’t plan particularly well when I made this.

It’s not so much a play on as an explaining the joke of the Half-Fast Walking Club, led by jazz musician Pete Fountain until his death in 2016. I have been a half-fast walker (among other things) for much of my life, especially as I’ve gotten older, so while I have never been a member of the Krewe, I feel a hard kinship with them. If anyone in central Iowa sees this and wants to start up an unofficial satellite group, hit me up, especially if you’re a Louisiana expat like me.

But this year, no matter how much Professor Longhair and Dirty Dozen Brass Band I played, I have just been having a hard time getting fully into the mode. Watching the government you grew up with and felt you kind of hand a handle on how it worked start acting like a washing machine with a bowling ball in it can do that to a person. (Go find that video if you’ve never seen it before.)

My favorite individual day of the season is always Lundi Gras, the day before the big one, and anyone who’s ever lived in or near a tourist destination can already tell you why. The big tourist days for Mardi Gras are the day itself and the Sunday before. That’s when the biggest parades run, that’s when the traditional debauchery is running at its strongest, and you gotta really want it to get out there in the middle of it, especially if you’re protective of your local flavor.

But Lundi Gras has that eye of the storm calm, where you can almost convince yourself that the tourists are all still recovering from Sunday so they won’t be yelling in your face, where you feel like you can get close to some floats and catch some throws, where even the Bible-thumpers with their big signs about all the different kinds of sins that will send you to hell are chill by their standards. It’s not safe, to be clear, but it’s not as raucous as the big storm either side of it on the calendar.

At least that’s how it was when I lived there. I’m sure it’s changed. Everything does.

But something changed yesterday for the better in my small world. My oldest daughter, also a child of the region, is a baker, and this year convinced her boss to let her try king cakes, and she brought one of the test cakes over after work yesterday and when I tell you my heart lifted and the clouds parted and the angels in midheaven sang praises, well, I’m underselling it.

Oh my god, y’all. She’s going to be doing the regular cake, and also with cream cheese and praline fillings. This was the praline, and I do believe that I would elbow an old woman in a walker to the ground to get at it if it’s the last one in the store. I hope it won’t come to that, and I also hope that y’all will have bail money for me if it does.

It’s more than just the cake though. Part of the reason I haven’t been back to Louisiana much for the season or for any part of it is because now when I go back I feel like a tourist, or maybe a half-assed tour guide. I don’t really have people there anymore.

When I finished high school, I mostly fell out of touch with everyone I went to school with. I was a Jehovah’s Witness and they weren’t, so we were mostly friends because we were just around each other every day. The Witnesses actively discouraged making relationships with non-Witnesses, which is what most cults and cult-adjacent groups do. The idea is that members of the out group can never really understand what you believe and can only undermine your faith, so you need to avoid them.

When I got married a couple of years after that, I moved about 40 miles away where I didn’t know anyone, so all my friends were members of the church, and when I left the church six years later, well, that meant I didn’t really have anyone left that I had deep ties with. I had college friends that I made over the next three years, people I waited tables and slung drinks with, people I wrote with and so on, and I’m occasionally in touch with some of them, but I don’t feel like I could ask to crash on their couch if I was coming through town. It’s not like that with them.

So if I’m going to New Orleans or the Northshore, I mostly feel like a tourist, only instead of famous places I’m looking to see if a restaurant I used to love is still there, if I can recognize my old neighborhoods where I made questionable decisions that maybe I don’t want to explain to my kids so what are we doing here anyway there’s nothing to see who wants a sandwich?

What’s missing is family. If family isn’t there, then it can’t be home anymore, and that’s regardless of whether it’s family by blood or made family. Family is where my sister is. Family is south Florida and St. Albans and Lyon and Valence, where Amy’s people made me one of their own a long time ago. Family is in Athens, Ohio and Ithaca, New York, with some friends we don’t see often enough. Family is here in Des Moines.

But Louisiana is still home in my memory and experience and I try to keep it alive here for myself and my daughter and others. So for the next week “Claiborne Street is rocking from one side to the other / the joints are jammin’, packin’, and I’m about to smother / all because it’s carnival time.” Thank you, Al Johnson. Thank you, Gambit and Chewbacchus, the Dirty Dozen Brass Band and Dr. John, the Mardi Gras Indians, Miss Annie and Miss Patsy who taught me how to cook Louisiana food at Happy’s Fried Chicken and Biscuits when I was a teenager.

Usually for these pieces I have a poem that drives what I write about in the first part, but I knew all along that I wanted to write about Mardi Gras and being separated from home, so in this case I went looking, and I had a really hard time because from what I could tell, there just aren’t a lot of poems specifically about Mardi Gras. Not according to Google, anyway, though that could be them.

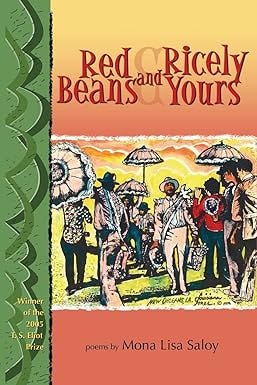

On the plus side, the search meant that I discovered work by Mona Lisa Saloy, who I’d never heard of before though I really should have given that she’s a New Orleans native and a professor at Dillard and was Louisiana Poet Laureate from 2021-2023. The book this poem comes from, Red Beans and Ricely Yours, won the 2005 T.S. Eliot Prize and was published by Truman State University Press. From what I can tell, this is the only place the poem has been published, and I doubt I would have found it without this piece about it by Stacy Balkun at the University of Arizona Poetry Center.

The poem’s title is “A Taste of New Orleans in Haiku.” It’s thirteen sections long, which also evokes Wallace Stevens’s “13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” for me, but only on a superficial level. Saloy’s poem is rooted in place and community, in flavors and family and local language. (The book has a glossary at the end to help readers with unfamiliar terms, and while I knew most of what she wrote about, I was glad to have it there.) Her first haiku reads:

i.

Mardi Gras Indians

red beans and rice, hot sausage

dancing Second Lines

The history of the Mardi Gras Indians is too rich and complex for me to do it justice here and I’m not even going to try. Most of what I know comes from the music, because many of the krewes are performers in their own right, and the songs are filled with references to their culture. Check out The Wild Magnolias, The Wild Tchoupitoulas, Big Chief Juan Pardo, Flagboy Giz and Big Chief Monk Boudreaux just for starters.

There’s a song called Second Line which I first heard when I was in 5th grade, Brock Elementary School, and I didn’t learn until later that it was also a tradition. It’s the dance-walk back from the cemetery after a funeral, where you start to celebrate the life of the person you lost, but it also has a broader sense of any celebratory dance-walk. You second line at a parade, you second line when your football team wins, you second line when your income tax refund comes in. The heart of it is finding joy in the moment because the moment is all you know you have, so grab it now, which is something Saloy gets at in section iv.

On Mardi Gras Day

skeletons remind all folks

you might be next yeah

Years ago I wrote a poem about the places where I’d lived that I loved most and what they all had in common was this sense that they might not be here tomorrow. I was talking about New Orleans, San Francisco and Fort Lauderdale, and about natural disasters, about hurricanes and earthquakes and sea level rise. I wondered if being faced with that possibility along with the real likelihood that everyone local had lost someone to a disaster meant that we reached for reasons to celebrate whenever possible. It’s more complicated than that, especially when race is a factor, but I think at some level it’s true. Take joy where you find it.

This poem jumps in subject from haiku to haiku, and the sections about home are spread out in the poem, but I want to put some of them together here for a moment.

ii.

Allelu Sundays

giving thanks, blessings, family

panné meat dinners

vi.

Red beans and rice day

washing clothes all day Monday

add French bread, salad

vii

Butter beans Wednesdays

Barq’s root beer a midweek treat

everyone’s home

The family meal is an important part of this poem and this world. One of the problems I had with holding onto the food I loved when I moved away is that so much of it only works if you cook it for a lot of people. You can’t really make red beans or a muffuletta or fry up chicken for one or two people. It’s too much mess and the recipes don’t cut down well and it doesn’t feel the same eating it by yourself in front of the tv. You need people talking and laughing and wanting more. It can be family born or chosen, but it needs family.

And that’s where Saloy ends her poem, with her father specifically.

xiii: Haiku for Daddy

His African heart

his Creole blue eyes, light skin

his core, New Orleans

I keep rereading this last section and focusing on the way Saloy manages in so few words to connect heritage and community and family in her father and New Orleans simultaneously. Pretty much everything in this poem is a mélange, from the multiple origins and traditions that make up Mardi Gras and the revelers to the big pots of food that simmer and stew until the flavors marry and grow to the people themselves who make up the community. It’s all a complex, complicated mix. It’s delicious.

According to a couple of places, you can still get copies of Red Beans and Ricely Yours and I recommend it as a book. Saloy has a lot of great poems in here. I’m using the copy I found in the ISU library, but I plan to buy one for myself soon.

Thanks as always for reading. I’d love to hear from you about the places you’ve made home, about your connections to the place or even if, like me, you feel like you’ve lost touch with some of it. Have you made a new home? How do you feed that? I won’t lie, I could use some advice on this, I think.

I'm always grateful to Dave for his round-up. This has been an inspiration this morning. Thank you.