I remember an all-day field trip to the Honey Island Swamp. Canoes, sack lunches brought from home with soda cans wrapped in foil, their tops distended from too long in the freezer. We wore clothes we didn’t mind ruining just in case. Near the end of the school year, eighth grade, most of us moving on to high school next year.

Though none of us lived near the actual swamp, we were old enough to understand the danger of where we were headed, far enough from roads and ambulances and hospitals and close enough to water moccasins and alligators that we needed to pay attention. We wondered aloud about what other beasts we might encounter—black bear, wild boar, somebody’s pet python they’d got tired of buying feed store rats for and just let loose—but what all the adults were most worried about was some of us getting lost.

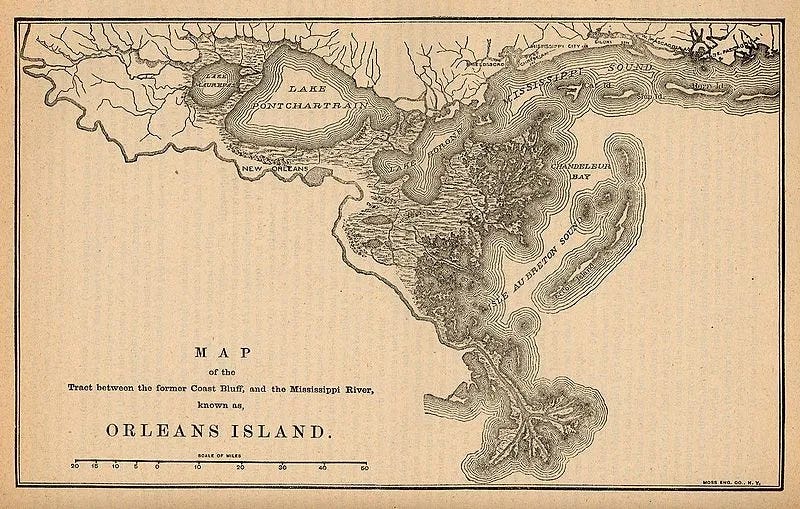

Our guide had contour maps of the whole area and he showed them to us but he also let us know that they weren’t all that helpful except for the broad strokes because the river made and washed away new islands on a whim, sluicing channels through islands that had risen up the week before. Every trip was a new one in a way. What had once been a channel wide enough for an air boat could catch canoes, and if you stepped out to push yourself free, you would probably lose a boot in the sticky mud.

From the teachers’ perspective it was a perfect trip. Nobody got in a fistfight, nobody got lost, and nobody tried to sneak off and get lost either, not even for a little while. Everybody got back to the school, bug-bitten and smelly and uninjured.

The swamp is a perfect place to get lost in or disappear into, depending on what you need, which is not to say doing so is a smart idea, even if you know how to get lost in a swamp. Most of the stories I have heard in my life about people who took to the swamp involved desperation, even the more romanticized ones.

The popular conception of who lives in the swamps of south Louisiana is of the Cajuns, and I honestly don’t know how much y’all actually know about Cajuns, and by y’all I mean all y’all because I cannot count the times I’ve told people not from Louisiana that I’m from Louisiana (specifically the New Orleans suburb of Slidell) where they’ve replied “but you don’t have a Cajun accent.” To which I politely reply “oh, no, Cajun country is further south and west” but really what I want to say is something I’m not going to put into this post. My gut tells me that when most Americans hear the word Cajun they think of Tabasco sauce, Cajun Pawn Stars and Gambit from the X-Men.

And I’m not here to talk like I’m some great expert on Acadiana and the people from the area. I am absolutely not. I just know enough to realize that.

The very simplified story goes that after the 7 Years War between Britain and France, the Acadians were expelled from Nova Scotia and some of them made their way south to the French colony of Nouvelle Orleans, and many of them moved south and west from there into the Atchafalaya Basin, which is not all swamps. There’s a lot of agriculture in that area—sugar cane, rice, soybeans—as well as ranching, and during the oil boom of the 70’s a lot of the locals went to work on the oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico.

But there’s also a lot of swamps, and if you’re the type of person who wants others to leave you alone, a swamp is a choice, especially if you’re still friendly with or related to the people on the edge of the swamp who have access to things that make your life a little easier in harsh conditions. And there were and are s fair number of people in that area who still want to live that life.

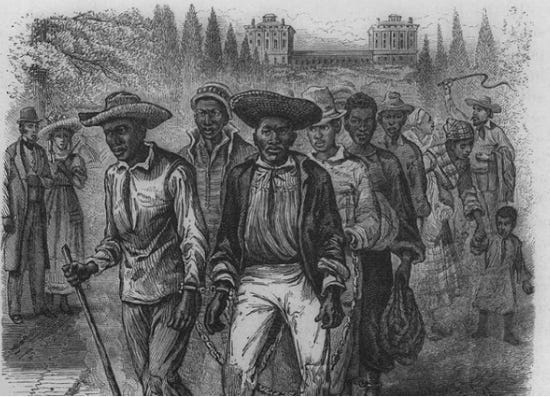

But swamps have historically also been homes to people who need to disappear or at least relocate from their current arrangement, and who have people looking for them. People on the run, let’s say. Okay, enough with the euphemisms. For long periods of US history, swamps were homes to people who were trying to escape from slavery.

These people came to be known as maroons and they formed settlements throughout the deep south as well as in Virginia and the Great Dismal Swamp. These settlements were isolated and hidden and it’s not exactly clear how much independence these groups had. There’s some suggestion that nearby whites would leave the maroons alone and even trade with them, but more often the powerful whites, who lived in constant fear of a slave revolt, tried to use military force to capture the maroons, either re-enslaving them or executing them.

The first stories I remember reading about these groups was about the Black Seminoles in Florida, mostly in the context of the Seminole Wars (yet another reason to get Andrew Jackson off of US currency) but I feel it necessary to point out that I learned about these groups as an adult, and not like a young adult either. Less than 20 years ago, certainly.

Why is that important? Well because it wasn’t until I had decided to write about the poem I’ll get to in a minute that it even occurred to me to wonder if there had ever been maroon settlements in the Honey Island Swamp, the place we went on that field trip in eighth grade, the very year we were studying Louisiana history.

Get ready to be not surprised. This is Jean Saint Maló, a maroon who escaped from a plantation on the Mississippi above New Orleans.

His main camp was in Bas du Fleuve, along the banks of Lake Borgne but he used the entire area around the Rigolets to operate in. He and his party would occasionally raid plantations and kill cattle, but they mostly tried to produce food and goods for trade. When they engaged in violence, it was mostly defensive, but they were still considered an existential threat to the slave-owning whites in the area who at this time (the 1780’s) were largely Spanish. In 1784, the Spanish colonial government captured Maló and executed him.

I’m going to quote some from this piece by Chris Dier, 2020 Louisiana Teacher of the Year and National Teacher of the Year Finalist.

His legacy helped inspire the German Coast Uprising along the Mississippi River in 1811, the largest slave insurrection in United States history. San Malo did more than inspire hope for a life of freedom for the enslaved. Sometime between the 1820s and 1830s, a Spanish ship leaving the Spanish East Indies, present-day Philippines, docked at New Orleans. A group of Filipinos seized the opportunity to abandon ship. These Filipinos, skilled and adept at life on the water, sought refuge on the shores of Lake Borgne, in modern-day St. Bernard Parish, away from the hustle and bustle of one of the largest ports in the Americas. They named their newfound settlement Saint Malo after hearing stories of the legend. It was the first Filipino settlement in the United States.

Turns out that some of those Filipinos and their descendants were recruited by Jean Lafitte, the pirate who supported US forces during the Battle of New Orleans (under fuckhead General Andrew Jackson) in the War of 1812, or more accurately, after the War of 1812 had ended but before anyone in New Orleans knew it.

That sounds like the kind of thing you might expect to learn about in a Louisiana history class, right? Maybe? It’s been a long time but I believe the only time we learned about a slave revolt in my history classes it was Nat Turner and there was a lot of focus on how mean he was to white people. Nothing about why enslaved people might want to rebel or escape, nothing about their treatment or what it meant in practical terms to be owned, considered property by another. And certainly nothing about the lengths that slaveholders were willing to go to in order to preserve their wealth and status.

Just now I looked up Saint Malo, Louisiana, to see what I could find about this place founded by escaped Filipinos. (Here’s a link to the historical marker for the site.) It was washed away by the New Orleans hurricane of 1915. I don’t even know what to say about this, except that it fits, I guess. The water continually remakes the landscape and if you don’t have the power to rebuild, then you mostly disappear. What histories have we lost?

This journey for me started because I read January Gill O’Neil’s latest book Glitter Road and while I could have chosen a dozen different poems for this newsletter, I went with this one titled “The River Remembers,” first published on December 27, 2021 in Sierra, The Magazine of the Sierra Club. The publication date and her bio suggests that this poem was probably written while she was the 2019-20 Writer in Residence at the University of Mississippi, Oxford, and I really enjoyed seeing this landscape through her eyes.

The poem begins “Here the water is silt brown / stretches mile-wide, / flat as a washed-out conveyor belt.” I feel like I’ve been here, both on the river and with the conveyor belt from my days working in a grocery warehouse, the flatness disappearing into the distance, the heat engulfing you, not quite smothering but let the sun crawl past noon and the humidity come up a couple more points and you’ll be sweating without moving. Even the lukewarm water of the river feels cool then.

I can’t read the River, can’t see my hand

when it plunges elbow-deep

to feel the cool against

the Mississippi heat—

hot as a dog’s mouth.

That last line is so perfect. I’ve never made that connection between the unrelenting hot-wetness of a summer day in the south and the slobbery mouth of a dog.

They’re canoeing on the Mississippi, it seems, which means they’re dodging river traffic, “trash barges and tugboats,” but they’re also far from population centers.

Farm, farm, tumbledown shack.

Creeks and rivers bifurcate the land like blood veins.

Here the GPS gives up.

That line made me laugh the first time I read it, because while I remember clearly times in my life where it was easy to get lost in the country, I’ve also gotten used to the idea that the little computer I carry in my pocket will always know where I am, so the idea that I’d look at it and it would give me a shruggie is hilarious. The poem continues:

New islands form at the current’s whim

and what is untouched grows lush and verdant.

Willow and privet border the collapsing coastline.

A carp leaps into the boar when it hears us coming.

We stop here in an oxbow, gumbo mud sticks to our feet.

River rock. Plastic. Fossils. Gar.

Raccoon and coyote leave tracks in the rust-colored sand.

That’s such an interesting collection of objects on the riverside to me. River rock predates anything else in the area, even the river. Gar are practically living fossils, but in the middle of it, plastic which is man-made but may outlast everything around it. And then, on the next line so separated from the list, are what’s alive today, raccoons and coyotes, going about their lives.

The slaves—sold down the river—hid here,

waited for their chance to escape up north,

hid in caves, fled to the Twin Cities and Canada,

their fate at the mercy of the river’s next rise.

One of the other things we weren’t taught about much in school (beyond the existence of Harriet Tubman) was just how hard it was for enslaved people to get far enough north to start new lives. I remember being surprised at learning about how many of them who managed to get out of the deep south then had to keep going all the way to Canada because the Fugitive Slave Law meant even the North wasn’t safe for them.

But it wasn’t until I was much older that I learned that being “sold down the river” was often a punishment for recaptured escapees. It was harder to get north, especially over land, from deeper in the south. That’s no doubt part of the reason why maroon communities developed. When faced with the choice of either a dangerous overland journey north through an unfamiliar and hostile landscape or trying to stow away on a ship and successfully hide for the length of the trip up the Atlantic coast, living in the swamp adjacent to the places and people you know might seem like a solid option.

The poem closes with these lines:

Here’s the nadir of our suffering,

which started in one place to end in another.

Here’s where flow and marvel and history converge.

This harmjoy. This beautiful sadness.

Look at how the word “our” simultaneously expands and contracts this poem. The entire poem has been in this first person plural voice, but it’s read like the speaker is in the boat with another person, and the reader is listening to them recount the trip. But “our suffering” is expansive in that it refers to a much larger group of people, the descendants of the slaves who hid in and lived in these swamps, along these riverbanks, in hopes of grabbing freedom for themselves and their people.

But it contracts the poem as well, at least for someone like me, and to be clear this is a good thing. As a white southerner, I’m not part of this group. My Irish ancestors might have fled poverty and persecution (I say might because I don’t actually know why they came here, but it was a common story) but they were never enslaved or treated worse than freed black people after the Civil War no matter how much white supremacists try to claim it. Irish immigrants had it hard in a lot of places but never like this.

I can bear witness to that suffering, to that harmjoy and beautiful sadness, but it’s not mine. And in some small way, maybe I can help bring attention to the ignored and erased stories of these people who risked everything to try to get free.

Thanks for reading, as always. If you have stories like these, I’d love to hear them or read about them.

This is a lovely post. Thank you for sharing it.