Near the end of spring break in 2020, back when we thought maybe we’d be able to control Covid with a couple of weeks of lockdown, my uncle Dave went into the ICU and straight onto a ventilator. Over the next two weeks, he died twice and was resuscitated, but eventually recovered. He was the baby, the youngest of six on that side of the family, not that much older than me. When we were both kids and I’d visit, he got a kick out of making me call him uncle in front of his friends.

While he was sedated his brother Joe, the next-youngest, died of a stroke. This was early April when testing was just becoming a thing that medical workers could get access to and YouTube was filled with videos showing you how to create makeshift masks out of old t-shirts and emails/texts about how sipping hot tea every 30 minutes would wash the virus out of your throat and into your stomach where the acid would destroy it. Good times.

It’s hard to mourn relatives you don’t know. I wasn’t particularly close to either of those uncles before I left the Jehovah’s Witnesses in my mid twenties, but once I’d done that, everyone who was in the church cut me off. The group texts I mentioned above? They started before the pandemic to keep everyone apprised of my grandmother’s health, especially once she went into a nursing home. I replied to a couple of them but no one responded and eventually I stopped trying. It felt like I was included as a courtesy.

How do you mourn someone who doesn’t acknowledge you’re alive?

I keep coming back to that moment where my uncle Dave comes out of sedation having no idea how long he’s been out or what his body has been through and one of the first things he learns is that his older brother is dead and that the thing that put him in the ICU for two weeks and nearly killed him is spreading and will soon ravage the entire planet.

I can’t ask him, of course.

I keep distracting myself while I’m trying to write about this. I tell myself I need to look something up on my phone and then I look at a bunch of other stuff until I shame myself into putting it down.

I don’t really want to write about it yet. I might never want to, so I’m forcing the issue. I have to write about grief, not for y’all, but for myself. Because I have to admit to myself that I haven’t really grieved for any of the family I’ve lost.

My dad died just over nine years ago, almost 3 weeks to the day after my twins were born. I learned about it while I was changing flights in Denver on my way back from the AWP conference in Seattle. It wasn’t a surprise. My sister had told me that his doctors said he had 2-3 days left and they were correct. He had dementia and the last phone conversation we had was about three minutes long in content and fifteen minutes long by the clock, and it was pleasant enough as these things go. I don’t know if he remembered the reason we hadn’t talked for years but it didn’t come up.

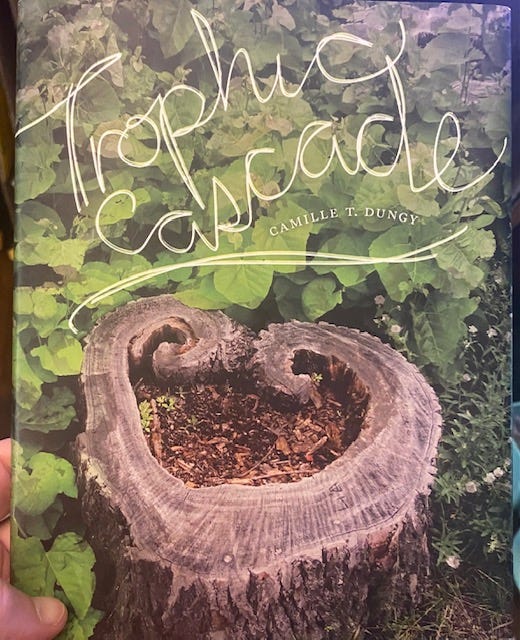

But no matter how much I don’t want to write about any of this, there’s no avoiding it. That’s what the title of this poem points out. “Notes on what is always with us” is from Camille Dungy’s 2017 book Trophic Cascade (Wesleyan University Press) and first appeared (in slightly different form) in the Fall 2014 issue of Blackbird. It starts with this line: “This week I threw a birthday party for my mother, and grief came along / for the cake.”

That second line is such a punch, “for the cake” set off like that. In the book, it’s indented so that the for’s line up one beneath the other, so you get “for my mother” over “for the cake” and you couldn’t have more of a contrast there. The party is done out of love and a desire to celebrate, but to show up for the cake is to show up for the least interesting part of the event. We took our daughters to a birthday party this weekend and the cake was practically an afterthought. To be fair, we were at one of those places that’s practically wall-to-wall trampolines—I did not jump as I would like what’s left of my knees to retain some stability and function—but still, the fact that nine year old kids were not laser-focused on cake from the start kind of proves my point.

I can hear you though. Brian, what would you expect? Of course grief is a shitty party guest. It’s not there to compliment the china or the chocolate fountain or the bespoke bourbon. “We asked grief to be quiet, but she smiled, smacked her lips, / and tore into her steak.”

After my dad was cremated my sister asked me if I wanted some of the ashes and I said yes because I didn’t know what to say and to say no would have felt churlish I guess? But I also had no idea what to do with them. I still don’t. They’re on a high shelf in my home office beside the ashes of three of our cats. I feel guilty any time I glance up there and see the case that contains the tiny urn with some of what’s left of him in it. I don’t know how to properly and politely deal with the fact that a part of my dad, a man who barely spoke to me for almost the last twenty years of his life because I didn’t believe in God the same way he did, sits on top of an Ikea bookcase in my office over my left shoulder because I don’t know what else to do with it. I should talk to my therapist about this. More. Again. I think I have an appointment this week.

The second section of “Notes on what is always with us” takes us to Antarctica and tells us that “On land, adult penguins have no natural predators.” Camille writes a lot about nature. The title of this book refers to the effect that predators can have on an ecosystem that limits the density of their prey and so makes it easier for organisms lower down to exist and even thrive. The example I’m most familiar with is the one from Yellowstone where reintroducing grey wolves cut down the deer population which allowed plants that had been eaten nearly to death by over-grazing to come back, which brought back all the animals that used to live in and off of those plants and so on, thus bringing back the biodiversity of the area that had been lost when the wolves were removed. A lot of that is in the poem by that name which appears earlier in the book too. You should buy it.

But back to the penguins. On land, and I have to admit I didn’t know this before re-reading this poem recently, adult penguins are relatively safe. Their biggest predators are in the sea, namely leopard seals and orcas. Chicks and eggs have to be protected, but adults are pretty cool. On land.

I am trying to write about penguins, about predatorless terrains.

I am trying to write about joy and a kind of cold beauty,but grief won’t stay away.Grief will ride in on the smallest of bodies,

a tick on a cormorant’s wing.

The possibility of a global pandemic like the one we’re still coming to grips with was on the minds of a relative few when Camille Dungy wrote this poem, and most of them were probably people paid to think about those possibilities specifically. What I mean to say is that while for some of us, for me, this current swell of grief is connected to that tidal wave of loss we’re all still trying to come to grips with, the truth is that there’s always lots of us in some level of pain over loss.

I lived deep in the woods for a couple of years as a kid, on the back side of a ten acre lot in Big Branch, Louisiana. We’d inherited a dog from my aunt when we moved there, a German Shepherd mix she’d named Sharezer, which is a deep cut from 2 Kings, and he lived outside which meant he needed fairly regular treatment for ticks and fleas. Well, for ticks, because living outside in the woods in the mid 1970’s meant there was no effective treatment for fleas. And for ticks, the treatment our neighbor prescribed involved pulling them off by hand after holding a lit match near the skin so the tick would detach before we pulled it off. And then crushing the tick either in our fingers or under our heels. Until I typed those words I had never really thought about how disgusting that is, because why would anyone ever think about that if they didn’t have to. I was told we did that because otherwise the tick would lay its eggs in the dog and we’d have more to take off. I have no idea if that’s true and if you don’t mind I’m not going to go looking for answers. I don’t need the invitation to distract myself here.

My point is that the ticks would latch onto Sharezer’s skin and then gorge themselves on his blood and I really have no idea how uncomfortable it was for him, though if this poem is any indication, it was terrible.

If the winter isn’t cold enough to kill it, that tick will embed itself

in a penguin’s neck, the back of her head, anywherethe penguin cannot reach,and because she has no way to tell anyoneand because, even if she could convey her agony,

there would be no way for her fellow birds to help,she will itch for awhile, swell for awhile,

then abandon her nest for the water’s relief.

She will run and slide and dive into danger.Her eggs will die and her chicks will dieAnd she may die as well.

This is one of those “there but for the grace of whatever go I” moments for me because while I have never been so overwhelmed by pain that I would dive into whatever serves as predators for me I can understand how a person gets there. My mother may think I have done just that, by fleeing the church I was raised in to swim among the satanic orcas that have been batting me out of the water pretending to let me escape before gathering me back eventually to devour me when they’ve grown tired of their fun. That metaphor works way too well the more I think about it. Jesus Christ.

I’m not going to get into the doctrine of the Jehovah’s Witnesses and the way it can cause really fucked up family relationships in this piece, but you can bet that it’s coming eventually.

I try to write everything down, because I know it would be easier

to forget and I want toavoid the comforts of suppression

That’s how the final section of this poem begins and it’s true. There’s a poem by Miller Williams which, if you talk to me about poetry for any length of time I will eventually bring up titled “Let me tell you,” and the third line is “First, remember everything.” It’s an Ars Poetica but it never explicitly gets to the reason why we need to remember the way Camille’s poem here does. “Because I know it would be easier / to forget and I want to / avoid the comforts of suppression.” The trick is that forgetting isn’t all that easy either. All of this is hard, the experiencing, but also the remembering, the processing, the forgetting. However we wind up reacting to loss is hard.

At the beginning of the pandemic I tried to write. Start writing again is maybe a better way to put it. I hadn’t been doing it much before then and I can give you a list of reasons why but they don’t matter. What matters is that before we were facing who knows how long indoors and away from others as much as possible I hadn’t been writing and now faced with it I tried.

It lasted maybe two months. Probably more like one. And that was even though I’d told myself going in that I wasn’t writing with an eye toward publication. I went in expecting that I would never send these poems to anyone except the people they were written for, or to. I wrote poems on postcards and sent them to people who didn’t really know me as a poet primarily. I sent one to my sister, two to my grandmother in the nursing home, one to my mother-in-law and one to my eldest daughter. And one to my mother, who never acknowledged that she got it. It was about a memory from my early childhood, maybe when I was four years old, when our relationship was so much simpler.

I was trying to write about beauty, but grief won’t stay away.

I was trying to write about babies and birthdays and birds.I was trying to write about joy.

In my case it was about a red-and-white trailer and a roadside burger stand with a jukebox and a root beer float. It was also about joy.

My grandmother died in August of 2021 of natural causes. I attended the funeral on Zoom, the way I’ve attended all such things for the last 3 years. I took my tablet to the cemetery a few blocks from my house and sat under some trees while an elder from some congregation gave the same talk that I’d heard at my uncle’s funeral on Zoom the year before and that I’d heard over the phone at my father’s funeral 8 years earlier and it felt just as empty of meaning as it always had.

That was the tick in my neck, though I didn’t make that metaphoric connection until recently. But because I am not a penguin, I was able to get it out. It took some help and there are some scars, but the tick is out of there and I’m not diving into the ocean to find temporary relief.

If you’ve read this far, thank you. I mean that earnestly. This is a lot and I wouldn’t blame anyone who tapped out at any point. If you have favorite poems about grief or loss, I’d love to read them, even if (especially if?) they’re ones you’ve written.

I don't have a poem to share though I will make a call that I've been putting off as a result of reading this. It's unremarkable though no less painful that folks wronged are often the ones that have to do the heavy emotional lifting. 'You carry it," folks seem to say, when the burden is rightfully theirs to carry or at least to shoulder part of it. Sorry you have to go through that estrangement from your family. I know about family estrangement though the cause is different in my case. Actually, I do have a grief poem making the rounds now though I didn't think of it as such before now. It's a take on the Eurydice myth. That wanting to hold something/someone close but it keeps slipping away. I'll share it once it finds a home somewhere. Anyway, thanks for sharing this poem. I'll look for the collection.

Beautiful, heart-breaking entry, Brian. Thank you so much for posting it.