When the first thought isn't always the best thought

On Matt Donovan's "Here the Thing with Feathers Isn't Hope"

The first and so far only time I fired a gun was when I was a kid. Maybe a teenager but I don’t think so, not quite. We were visiting my uncle Bee in Tennessee and one night, not long after dark, he asked us if we wanted to shoot his gun. It was a pistol. Maybe a .38 or a .357. I don’t remember much else about it except how big it felt in my hands and how much I wanted to shoot it well. Bee set up some empty beer cans some ways away in the yard—he lived on a sizable piece of property in a very rural area; the closest neighbors might not have even heard the shots, much less worried about where they came from—and I aimed and pulled the trigger. I missed, of course, as did my cousins who also took their turn firing a single shot each, and then Bee took the gun and sent the cans skittering through the grass.

It was louder than I thought it would be, I remember. My experience of guns up to that point was from TV shows and movies. I had lived a fortunate life.

The next time I had an up-close experience with a gun was when I was in my late 20’s, riding my bike home from work at a Mexican restaurant. Short version is some teenagers rolled up beside me on their own bikes, pulled a gun on me and stole my bike and my empty wallet. Just typing this I can feel the cold barrel on the back of my neck and the gravel in the pavement on my right cheek and the palms of my hands. I came out of it physically unhurt, and that’s where I’ll leave it.

The next time I heard a gun fire was the first day of my second year in graduate school and I didn’t recognize it for what it was. I wrote a poem about it eventually. I’m posting it below. I may come back to talk about it more, but not right now.

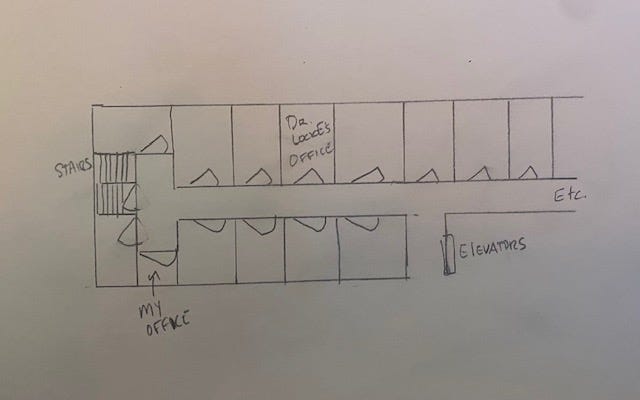

Okay I might as well talk about it now. The first day of my second year in graduate school. I’ve taught one of my classes and I’m hanging out in the office with my friend Paul talking about whatever and I’m getting ready to go up a couple of floors to teach my second one and I hear the above-mentioned noises that to me sounded like a metal shelf hitting a tile floor and a voice yelling “help! Help!” And I’ve never talked to Paul about this exact moment but I suspect he knew what that sound was because the look on his face was the definition of oh shit. Around this time, maybe just before, another voice down the hall said “he’s got a gun” and the order here may be off but it’s a blur and it’s been twenty-two years almost and then I’m trying to get in touch with the main office using the rickety intercom system because we didn’t have phones in our offices even though it was the goddamned twenty-first century and Paul is sprinting up the back staircase that’s right next to our office headed to the main office to tell them to call the police and there’s silence in the hall. Here, I’m going to draw it out for you so you can get a sense of the geography.

So that’s me and there’s the hallway and I’m thinking the voice saying something about the gun came from down by the elevators like five miles away. Okay more like 60 feet I’d guess, so I start creeping down the hallway looking to see if there’s anything I can do, put my hand in a wound or something I guess. I wasn’t thinking this through in the moment. And it does not occur to me that the gunshots had been in an office I was walking next to until I turn and see the door slam closed.

I hurry back to my office and because I don’t know what else to do I grab my bag and go up those stairs to the classroom where I’m supposed to teach and just stand there. When I was opening the door to the stairwell I saw a bicycle cop approach the door and knock on it. According to reports, there was one more gunshot but I wasn’t there to hear it.

The victim was Dr. John Locke, a professor who was about to retire, who I’d never talked to much but who was universally loved in the department. He had broken his ankle the winter prior, slipping on some ice, and for a while was in a motorized chair. He was peaceful and gentle by all accounts and had defended the student who would later murder him.

Friends and students of his placed flowers at the door of his office, which was also a crime scene for a while. I found ways to not walk down that hall for weeks.

I’ve heard others say, and I have repeated this to my therapist, that gun violence is like Covid in that there are few people who have not either lost someone to it or know someone who has. And if you add in the close calls, like how my mother-in-law, one of the most wonderful people on this planet, was at work at Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School on that day and left her phone behind when she ran for cover and so we didn’t know right away that she was physically unharmed, then I think you get pretty much everyone in this country, and if you are lucky enough to not know anyone in one of those three categories then I am very happy for you. I need you to know that I mean that truly.

My feelings about guns have changed a bit since I was that kid in Tennessee firing a single shot from a pistol more nervous that the gun would jump out of my hands and I would embarrass myself as a result than scared of the power I held there.

If you were to ask me today if I’m scared of guns, I would ask in return do you mean the gun as a machine, as a tool of destruction, or the gun as a rhetorical device, as a claim to power and dominance. Because the answer changes depending on what we’re talking about.

I have a healthy fear of guns as tools. A gun, when it does what it is designed to do, causes tissue damage and potentially death. When mishandled, whether because the user is careless or just because sometimes we fumble things, the gun can cause tissue damage and potentially death. I have the same kind of fear of a gun as I did of the forklifts I used to drive when I worked in a grocery warehouse. This thing can kill you or someone else, so respect it. Don’t be flippant when you have control of it.

I don’t fear the gun as rhetorical tool so much. I don’t even really fear the people who use it that way, who try to push back their feelings of powerlessness or loss or their own fear by loudly possessing guns. I say loudly for a reason. I’m talking about the “Come and take them” types who open carry because they like the way they think people look at them in public. I treat them warily and am cautious around them, but I don’t fear them because there’s no point in it. The people who worship guns and the power they think their guns project are in it for themselves. They don’t care how everyone else really feels because they have a fantasy of how everyone else sees them.

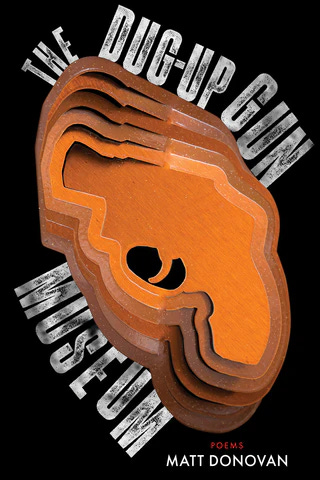

Many of those kinds of people make appearances in the book that I’m pulling the poem I’m talking about from, which is Matt Donovan’s The Dug-Up Gun Museum from BOA Editions last year. I think this is the first work I’ve read from Matt Donovan, who I’ve never met that I know of, but it’s his third poetry collection and I will certainly be looking for those other collections based on this one

.

The poem I’m writing about is titled “Here the Thing with Feathers Isn’t Hope,” which appeared in The New England Review in 2021 and which references Emily Dickinson’s poem “Hope is the thing with feathers” in which, and forgive me please for being so basic about one of Dickinson’s poems, hope is a bird which “perches in the soul,” which never abandons you and never asks anything of you in return. Matt Donovan’s poem, as you can tell from the title, is coming at this from a different angle. It’s one of those poems where the title is also the first line, so I’m including it in this first excerpt.

Here the Thing with Feathers Isn’t Hope

but a 400-pound pistol in the bed

of a pickup, welded together from

scrapyard metal & stamped with names

of kids shot and killed near the artist’s home.

And goddamn if that’s not a hell of a way to start a poem. I really like that Donovan uses weight to describe the size of the gun instead of telling us how tall or wide it was, because for a piece like this, the weight of it matters more than the size, at least for me. That it fits in the bed of a pickup is enough to give me a sense of its size, which also tells me that it’s got a lot of fucking names engraved on it. That gives it a different kind of weight, and the 400 pounds set me up to feel it.

We learn a few lines down that the artwork is called “Conversation Piece” and that the feathers that are affixed to it were a later addition, and I don’t want to presume too much about the artist here but I think I can get in his head a little about this because I’ve done something similar myself in poems I’ve tried to write about challenging subjects, in my case sexual assault, which I was the victim of as a young child.

1Here’s what I mean. When I write about something that’s really close and painful for me, one of the things I kind of want you as the reader to do is get close to it and really examine what I’m saying, and that’s in tension with the fear that I’ll frighten you off before you get to the important stuff. So I’ve tried to hold back and ease you in so you’ll be engaged before you realize what I’m really talking about. The danger is that maybe you’ll never see what I’m doing because the other images invoke some other response in you that overpowers what I’m trying to say.

Except for all the feathers, dyed

cotton-candy blue & affixed to the pistol’s

cylinder & grip, wrapping the length

of the barrel with a flourish like a boa

entwining a neck, it might seem like

any other oversized gun.

One thing I want to point out here is how the language of these particular lines is kind of direct, prosy, because I think that’s deliberate. The image of the names of victims engraved on the sculpture is the dangerous thing that tells us this is more than just a gun, but we’re not looking at it from the distance, say from across a parking lot or from the inside of our own car wondering what the fuck we’re looking at in the back of this pickup on the highway and wondering if maybe we ought to take a pit stop and let this guy get ahead of us a bit.

Back in the early 2000’s when the internet was first becoming a place where lots of people argued about politics, I saw firsthand the problem of trying to “send a message” to anyone, elected officials, interest groups, candidates, etc. It’s probably something that seasoned pros have always known, but I was learning on the fly. The message you send may not be the message they receive. In practical terms, think of someone saying “If we all refuse to turn out to vote for the compromise candidate, then they’ll have to listen to us for the next election” which maybe sounds not completely crazy until you realize the message the candidate/party might hear is “we can’t count on those people to turn out for us so we should look for votes somewhere else.” See what I mean?

This happens in art too. Sometimes it’s great. About 5 years ago now I guess one of my poems was selected by a filmmaker to be turned into a short movie for Motion Poems. I didn’t have anything to do with the production. The filmmaker, Ged Murray, never contacted me to ask me about what I meant to say. I didn’t see the finished product until just before it went live and it’s nothing like what I would have imagined. The woman speaking the lines of the poem in the film is a little more frenetic? unbalanced? Than the voice in my head when I wrote the poem. I was, if anything, kind of earnest in my poem, whereas in this film there’s a scene where she speaks one of the lines while sitting in a pub and the people at the next table get up and move. It’s amazing. I love it.

But my reaction to that experience may be the exception. The artist planned to drive this sculpture from place to place in the back of his truck.

But when he stopped for gas the first time

he knew his art had failed when a man

sprinted across the parking lot so say

Goddamn that’s one bad ass gun.

That guy was so amazed by the gun that he might never have seen the names engraved on it or wondered who they were, why they were there. And if he did ask, and there was someone to tell him, maybe he doesn’t react so well.

And so, the feathers have to go on as a way to make people realize there’s something more going on that just a big statue of a gun in the back of someone’s truck.

Something needed to change. Maybe

feathers could turn the pistol into

a thing you approached with a question

instead of praise.

And that’s a good thing for all of us to think about, whether we’re approaching art or an encounter with another person or what looks at first glance to be a dumbass post on social media, that idea of approaching something with a question rather than with certainty, whether we’re praising or condemning. Maybe there’s something there beyond the initial gut reaction.

The notes to the poem in the back of the book mention that the artist here is Garland Martin Taylor, and I’ve held off on posting pictures of the sculpture here because I wanted the idea to live in your mind for a bit. I only just now looked it up myself because I wanted the same for myself. I needed to ask myself how I would react if I saw, at a distance, a pickup truck with a giant pistol in the back. What assumptions would I made about the driver of that truck? How would the place where I saw it affect my reaction? Does it hit differently in a museum where there’s an expectation that an object is more than it initially appears to be? It has to.

This image is from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and was created by Yoni Goldstein.

This image is also from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the creator is not named.

Like I said above, if I was driving east on I-80 toward Chicago and I came up on a 4x4 with a galvanized steel toolbox and a 400 pound pistol pointing out the back of it, I might well decide to pull over for a while and let some space grow between us. I don’t know how many of y’all have ever driven that stretch of highway between the Iowa border’s amusingly named Quad Cities and Chicago, but there’s not much more than farmland for most of it, and still, sitting on the side of the road for an hour just waiting might seem more reasonable than sharing the highway with a vehicle that looks like that from a distance.

And if I saw it in a parking lot at say, a Denny’s, I might be tempted to take a picture from a ways away and then, if I were still on social media, post it with a quip that showed how much I didn’t know about it and then the internet would jump in to not just correct me but also yell at me and then I probably would stop being on social media afterward. But what wouldn’t happen, more than likely, is a conversation. Which is sad, because that’s what needs to happen more often than not.

I’m not the kind of person who thinks that we can solve all the world’s problems by talking to instead of at or past each other, but I do think we might make better progress than we currently are.

To everyone who has made it to the end of this piece, thank you. In previous posts I’ve asked you for poems that echo the theme of the poem I wrote about but I don’t even know what to ask for at the end of this one. There’s so much going on here. But please know that when you do suggest poems, I read every one of them. And if you want to share your own work in the comments, please do that too. I would love to read it.

In the poem, the sculpture is named “Conversation Piece,” but as the link from the pieces from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago show, the title is “Conversation Peace.”

Well, I just yelled, no, no, no! because I just accidently erased a comment that I spent about 20 minutes writing. It was about how a visit to a gas station today reminded me of the emotions that can accompany shootings. Fear, hatred, anger. The poem that came to mind after reading your piece was this Derek Walcott poem not because it relates to guns and shootings, but because it's the opposite of the kind of fear, hatred and anger that can be a part of shootings. Thank you for your essay and for the opportunity to share.

Love After Love

The time will come

when, with elation

you will greet yourself arriving

at your own door, in your own mirror

and each will smile at the other's welcome,

and say, sit here. Eat.

You will love again the stranger who was your self.

Give wine. Give bread. Give back your heart

to itself, to the stranger who has loved you

all your life, whom you ignored

for another, who knows you by heart.

Take down the love letters from the bookshelf,

the photographs, the desperate notes,

peel your own image from the mirror.

Sit. Feast on your life.

I loved the short film of your poem, by the way.